The Power Broker by Robert Caro, Pt. II

The story of how Robert Moses maintained and finally lost his power over New York

Hey everyone,

Greetings from Washington, D.C.!

Thanks for the incredible response to last week’s essay. It’s great to be back writing weekly and the best part about it is hearing your feedback and comments in response to my pieces. As always, I’m just a email reply away. If you are not subscribed, you can do it here:

This is part 2 of a two-part series on The Power Broker by Robert Caro. We pick up where we left off, with Robert Moses at the zenith of his power and influence. If you have not read part 1 of this two-part series, you can read it here.

The loss of the Battery Park Bridge battle did not affect Robert Moses’ power over the city. In fact, over the next two decades, Robert Moses would amass greater power and authority — absolute authority in most cases — over the public infrastructure that millions of people across New York would interact with centuries to come.

And if the veneer of invincibility had been scratched due to the fight — it was still largely intact. For while the reformers knew that it was Roosevelt who had defeated Moses, the complexities of how a President might influence the War Department to issue a report on potential bombings of a bridge over a water way and how that would hault the construction of the bridge was difficult for the public to understand. Moreover, the public still associated Moses with the magic word “parks.” And the magic word was now wrapped in a loom of public authorities and crisscrossing responsibilities — a loom which ensured that the mirage which was Robert Moses’ popular image would stay intact.

Why the press loved Robert Moses

And if there was a force in any democratic society which could have reigned in this false image, it would be the city’s press. But the city’s press were enamored with Moses.

There were several reasons for this.

One reason was that in the beginning of his career in the 1920s, Moses’ actions were actually beneficial to the public. Even if he did cut an unsavory deal with another powerful entity in New York, he did it to get things done — things which were useful to the public at large.

Another reason was the one that all journalists face — they had to fill pages. And no one’s actions filled pages better than Robert Moses’ building of public works. The sheer scale and speed of his efforts were so unparalleled — and largely remain so — that any journalist covering him would never run out of copy. There was always something to write about.

The last reason could be explained not by what he did, but when he did it. His first important post was as the Chairman of the Long Island State Park Commission in 1924. He remained in power until 1968. For most of that period in American history, there were plenty of cause for doom and gloom. The horrors of the Great Depression, the shock to the American psyche in the initial parts of World War I, and the first bouts of the Cold War. In New York, the problems were less psychologic and more financial in nature. The state was always strapped for money. If one looked at its balance sheet, one would not recognize it as the home to the economic capital of the world. It was in this context that admiration for Robert Moses is best explained. Here was a man who despite depressions, despite wars, and despite economic duress was building and creating public works. The sheer hustle and bustle against the backdrop of doom and gloom moved New Yorkers. And if the hustle and bustle moved its public, the effect it had on its journalists was no different.

This meant that while Moses’ actions were increasingly questionable, the overwhelming public feeling towards him was that of admiration.

The Political Machine of New York

He took full advantage of this admiration. And no where did he take more advantage of it than when it came to matters of his ultimate — and often only — goal which was the acquisition of personal power.

After the governorship of FDR came the mayorship of Fiorello La Guardia. It was a mayorship which starved the political machine of New York — a machine which was used to keeping their greedy appetites for money and power satisfied. And if the gravy train was out of service while La Guardia was Mayor, it promptly resumed service as soon as he left office.

And when the gravy train resumed service, Robert Moses was its coordinator, driver, and conductor all at once. From part I:

Each bridge, each parkway, each park, each beach, each public work poured in concrete created the foundation not just of the work itself, but of Robert Moses’ iron grip over the state and city governments of New York.

Everything in a project was a source of power.

Insurance contracts for a bridge he was building? Wouldn’t it be convenient if those contracts went to a key politician’s son-in-law’s insurance company?

Landscaping contracts for a park he was building? Wouldn’t it be convenient if those contracts went to a regional player’s landscaping company whose support Moses needed for another project?

Labor contracts for a tunnel? Wouldn’t it be convenient if those contracts went to a labor union which was opposing one of Moses’ works and would drop those opposition for a cut of the wages?

Robert Moses the idealist would have hated this dispensing of patronage. But that was no longer an issue — that Robert Moses no longer existed. Hating patronage? When it came to anything related to public works in the city or state of New York, Robert Moses was now the patron saint of patronage.

Each deal he made forged an increasingly stronger grip over his dominions. For if someone wanted to bring him down, they would have to bring down others. And while others might be sensitive to public opinion, his command of the several state councils and commissions were immune to public opinion.

Moses’ political mentor Governor Alfred E. Smith — who was the only person Moses would ever call “Governor” — had warned him that public opinion was “a slender reed to lean on.” Moses had internalized and codified that lesson into the statute books of New York State.

Reality Distortion Fields

This immunity to public opinion led to the permanent shaping of the New York Metropolitan Area towards the automobile and away from public transportation.

In 1900, when Robert Moses was 12 years old, the number of automobiles in the United States was 8,000. In 1903, it was 33,000. In 1912, the number was close to 1,000,000.

Growth trends like that are not associated with trends. They are associated with eras.

And at the beginning of Robert Moses’ career building public works in New York, the era of the automobile was truly at its peak. It was against this backdrop of high demand that Moses’ first projects were appreciated by the public. His highways and expressways were like a nervous system connecting organs across the New York Metropolitan Area. At the beginning of his career, when his power was not absolute and when he was not immune to public criticism and when the executive brand of the state or city government could have curtailed his influence, he learned that roads and bridges and highways were good and the public loved them.

But the public’s love affair with the automobile did not continue. The reason was simple: by the 1940s and 50s, there were now too many of them on the road. What used to be journeys characterized by speed and comfort turned into journeys which happened at a snail’s pace. Highways which were created to solve bumper-to-bumper traffic faced bumper-to-bumper traffic themselves.

There were solutions in sight. Automobile transportation is low-density. Relative to the space it occupies on the road, a car does not carry that many people. What is needed in a dense metropolitan area like New York are modes of transportation which are high-density. These are buses, ferries, and above all else, trains. In an urban context, this takes the form of a subway system.

Robert Moses was uninterested in building subways. He had grown up in the age of the automobile and he had no reason to believe that the public’s love affair had come to an end. His personal experience getting driven — the man who was perhaps the greatest champion of automobiles in post-World War 1 America famously did not have a driver’s license — was no different in the 1950s than the 1920s. It was comfortable for him back then and it was comfortable for him now. And if gridlock was a problem for the public, it was not a problem for Robert Moses. The isolation at the back of the car gave him a chance to catch on his work which now had ballooned to being responsible for more than a dozen institutions.

Effectively, he had a reality distortion field. And protecting this distortion was the political reality of his command of his various posts — no Governor or Mayor could just “fire” him. Protecting the distortion field was his physical isolation from the public — his home on Randall Island has its own infrastructure for transportation and enforcing laws. If the Pope had Vacation City, Robert Moses had Randall Island. And if the Pope had his Bishops, Robert Moses had his Moses Men.

And as time passed, protecting the distortion field was a factor not political or physical in nature, but one that was very personal — Robert Moses was going deaf. It’s not like he listened to anyone anyways, but now he couldn’t even if he wanted to.

And nowhere did this separation of his perception of the public’s needs from its realities become more apparent than when it came to his preference of highways over subways. In the 1950s, one of his big projects was extending the Long Island Expressway. The extension would cost hundreds of millions of dollars and while Moses did have the money, he did not have enough money to fund this and to fund all his projects.

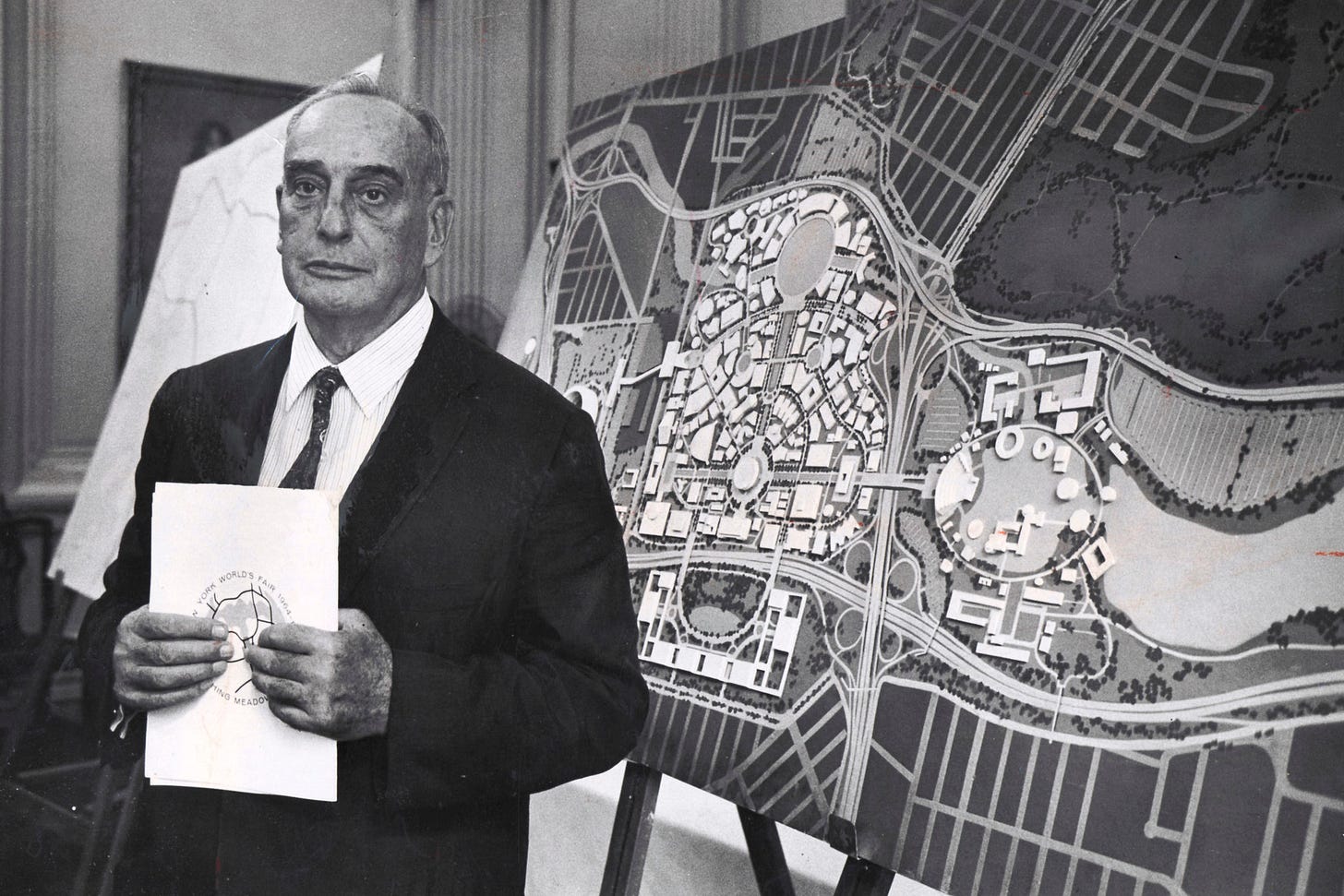

So he created an alliance. An alliance with the Port Authority of New Jersey. The Port Authority was another institution which was quasi-public like Moses’ Triborough Authority. But unlike Moses’ authorities, the Port Authority had no projects to pour money into. So Moses suggested a partnership which would benefit both of them — Moses would get his highways and the Port Authority would get to use its money productively (and get part of the toll revenue from its roads).

The expressway did not have a subway line. The expressway had no provisions for a subway line in the future. And not only did it not have a subway and no provisions for one, but it was built so it could never have a subway line. Were buses allowed on the expressway? There were not. And again, they were built so low that buses would never be able to traverse them.

Robert Moses, through the construction of the Long Island Expressway extension, destroyed any chance that Long Island had of a well-designed mass rapid transit system.

But these problems were to come in the future, and the present was on Moses’ side. Until he made a mistake which shattered the image that the public had of him.

The shattering of the legend

Robert Moses had always been associated with parks. But then he set out to destroy a part of a park. And note just any part of the park, but a part of the park where mothers brought their children to play together. And not just any park, but Central Park. And not for another park purpose, but for a parking lot of a private restaurant. And not just any restaurant, but a restaurant for rich people.

If the complexity of Robert Moses’ power over the city had been a problem before, now there was nothing complex about the situation at all. On one side were mothers, children, and the public trying to enjoy the only stretch of playground near their houses. On the other side was a private restaurant looking for a more convenient parking location for its wealthy patrons. And on the other side along with the restaurant and those wealthy patrons was Robert Moses.

The mothers protested. For the first time, the balance of public opinion based on the word “parks” was not on Robert Moses’ side. And in opposition to him the words “mothers” and “children” were added to the word “parks.”

But Robert Moses was not a man of words, he was a man of action. And if there was a challenge to his power, he would not tolerate it. He asked his crew to go ahead with the demolition of the playground and the construction of the parking ground. He won this battle like he had won countless before this one.

But there were a few key differences between this battle and the other battles. First, this was not a battle between parks and something else. It was very clearly a battle against Robert Moses’ preference for a parking lot of an expensive restaurants and mothers and their kids’ playground. Second, the victims of his decision were not helpless immigrants of a slum or poor residents of an apartment block which he had razed to build a highway, but rich families of the Upper West Side. Many of them had connections to the press. Lastly, it was on a location that was sacred for even the most cynical New Yorkers — Central Park. Any attempts — no matter how small — to change its landscape was seen affront to all New Yorkers. In this case, the public and the press saw Robert Moses as leading that affront for private benefit.

So even though he had won the battle, it was a Pyrrhic victory. The most important casualty of the battle was not the playground, but Robert Moses’ image. It was finally laid bare for what it — a carefully crafted image that hid immense naked and raw power which did not care for principles or the public.

In the court of public opinion, things would never be the same again for Moses.

Meeting Nelson (and losing)

But he was still shielded from it. For his authority came not from the whims of the public but from his command of the various public authorities and state and city commissions. No one, not even the Governor, could take all of those away from him. And even if he or she could take away 1-2 of these positions which were in his or her dominion, Moses would still have more than a dozen left.

But he could lose them. And that’s exactly what happened.

Nelson Rockefeller became Governor of New York in 1959. The scion of the wealthiest family in America had power, was accustomed to using it, and had a willingness to use it. And he had a ruthlessness in using it that reminded the New York politicians of another powerful figure — Robert Moses.

Rockefeller wanted to modernize the system of regional commissions which gave Moses so much power. Moses obviously did not want them to be touched. Rockefeller used the fact that Moses was turning 70 before the expiration of his next term as the head of a couple of commissions against him as public officials were required by law to retire at 65 unless extensions were given by the Governor.

Moses had always gotten these extensions before.

But Rockefeller wanted to make his brother Laurance the head of these commissions. So Nelson Rockefeller started to publicly say things like “New York State is fortunate to have Laurance Rockefeller following in the footsteps of Robert Moses” without consulting with Moses. Moses’ birthday came and with that date came the day Robert Moses could no longer serve on public authorities of New York State.

Moses had lost his first keys to power — the chairmanship of councils of parks.

And if he had age to blame for this loss, he would have nothing and no one else to blame but himself for the next loss.

He still had his public authorities. Being only quasi-public, they were exempt from the retirement age requirement. His command of these public authorities were based on bond contracts that the authority issued against the toll revenue of its works. If he was not the head anymore, its trustees could sue it on governance grounds.

Rockefeller wanted to subsume these authorities under a larger state authority — the Metropolitan Transportation Authority or the MTA. He needed Moses’ support for this. And he got it by promising Moses a position on the board of the MTA and by promising him that his public authorities would remain largely autonomous.

Nelson Rockefeller lied.

Once the legislation to subsume authorities under the MTA went through, Moses would not be appointed to its board and his authorities would not be autonomous.

There was a certain symmetry and irony to this fall of Robert Moses’ career. He had gotten his first taste of power through tricking state legislators into giving him broad authority over anything related to parks in New York State. He was stripped of all his power through legal trickery as well. The “best bill drafter in Albany” got a taste of his own medicine.

But there was another factor that was the final nail in the coffin of Robert Moses’ career. The bondholders which held the bonds of his authorities could still have sued the government for governance malpractice. But trustee for these bonds was Chase Manhattan Bank.

This, by itself, was not special — Chase Manhattan Bank had been and was to be the primary trustee of bonds for most of the public works built in New York. But there was one thing that was special about the current Governor and the head of Chase Manhattan Bank — they were brothers. And Nelson Rockefeller’s brother had no interest in suing him.

As Caro writes:

What was necessary to remove Moses from power was a unique, singular concatenation of circumstances: that the Governor of New York be the one man uniquely beyond the reach of normal political influences, and that the trustee for Triborough’s [the largest of Moses’ public authorities] bonds be a bank run by the Governor’s brother.

After 44 years of holding absolute power, the reign of Robert Moses was over.

The legacy of Robert Moses

Many of the ends of Robert Moses life were noble: the building of public works at the scale that he built them remains unparalleled and his model of quasi-public authorities became a model for more efficient governance for high-priority projects across the country. These ends would not have been a reality today were it not for Robert Moses. With today’s context, these ends are even more impressive — infrastructure projects in America today are notoriously slow and expensive.

But underneath this bright tapestry of unparalleled achievement run threads much darker in their nature. He was a racist — he kept the water temperature of the swimmings pool at his facilities cold because he had heard that African Americans only swim in hot water. He was a classist — one of the reasons why he didn’t like buses on his expressways which connected the cities to the beaches he had built on Long Island was because poor people were much more likely to come on a bus than a car. He was a dictator — immune to public opinion, he never sought it as reality diverged from his perception of the needs of the public.

And while Robert Moses would probably agree that the ends justify the means, the thousands of people he displaced from housing complexes would disagree. The millions of residents of the New York Metropolitan area who have to go to work every day in cramped quarters on subways would disagree. And the future generations bound to the tyranny of the concrete jungle that he helped shape would disagree.

But that does not mean that we should forget Robert Moses. For the real legacy of Robert Moses is as a cautionary tale of what happens when power is concentrated in a single man’s hand over the lives of tens of millions of people.

Until next Sunday,

Sid