Sunday Snapshots (9th February, 2020)

Netflix's origin story continued, Amazon's Antitrust Paradox, and Harry's merger blocked

Hey everyone,

Greetings from Evanston!

On Friday, I went to The Allure of Matter exhibit at the art gallery Wrightwood 659. It’s an amazing display of how old and new materials can blended together into spectacular sculptures. If you’re in Chicago between now and early May, I highly recommend you check it out. Pro-tip: they release free tickets every Tuesday so get on their mailing list here.

On to this week’s issue of Snapshots in which I want to explore:

Netflix’s origin story continued

Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox by Lina Khan

FTC’s blockage of Harry’s acquisition

Gorgeous movie posters by Matt Needle

And more!

Book of the week

Last week, I talked about Marc Ranolph’s book That Will Never Work about the origin story of Netflix. My takeaways were largely from the first half of the book. I wanted to return to the book and talk about the second half because I think it’s even better than the first. Let’s dig into them:

Know when you are not the right person: The single most powerful chapter of this book is titled “I’m Losing Faith in You.” In it, Marc goes through the experience of being relieved of his duties as CEO by Reed Hastings. Everyone agrees that the person who is ideal for one stage of the business (starting it up) is often not ideal for the later stages. But it takes real humility to come to that conclusion. It is difficult to express in words how important this chapter was to my overall experience of the book. It’s a testament to Marc’s humility and a blueprint for letting go of your ego for the larger mission.

Maximizing coverage: If you’ve been a long-time subscriber, you know that I’m a bit of a logistics nerd. But I didn’t know that Netflix created one of the first peer-to-peer shipping networks:

Turns out you didn’t need to build huge, expensive warehouses all across the country to ship DVDs if 90 percent of the DVDs people wanted were already in circulation. Tom had applied to shipping a principle we all understood intuitively: when it came to movies, people were lemmings. They wanted to watch what everyone else was watching. If you’d finished Apollo 13 yesterday, then it was highly likely that somebody else wanted it today. Conversely, if the next movie in your queue was Boogie Nights, it was just as likely somebody else was returning it that day. Tom’s brilliant idea was to recognize that when a user mailed a DVD back to us, it didn’t need to go to a warehouse the size of a Costco. It didn’t even need to go back on a shelf. It could go right back out the door to someone else!

Role of luck in success: Netflix could have been acquired by Blockbuster and Amazon. In the early 2000s, Blockbuster controlled the video rental business and it was becoming increasingly clear that Amazon was going to be a juggernaut. Netflix wanted to sell themselves to these incumbents. The fact that the incumbents didn’t buy the company seems like a ~$150 billion mistake in retrospect but doesn’t fully appreciate the very real problems that Netflix had. If Netflix had stuck to their original business model, they would have certainly failed. Ultimately, a paradigm shift towards streaming is what saved them. It’s a great reminder that young companies are often flying blind and that their radar is calibrated to the old world. In order to land successfully (or keep flying), they need a decent bit of luck.

Pivots: If you think about the Netflix story, it’s a story of constant change and evolution. They started off with being dependent on DVD sales, then decided that they would never be profitable doing that and pivoted to DVD rentals. This ended up being popular but made unit economics more difficult as they found themselves paying too much for acquiring customers they didn’t retain. They then had to develop a subscription model to create real lock-in and engagement. Obviously, they ended up pivoting from DVDs to streaming as well. The arc of success is long, and while great leaders like Marc and Reed can make it bend faster towards success, they can only do so to an extent. Continuous assessment of the current strategy – and having the courage to make the painful pivots – is necessary for success.

I wrote last week that the book is a “timely” one “with timeless principles.” This week, that view has been strengthened. I think That Will Never Work will be one of the most important books of 2020. I highly recommend you pick up a copy.

Long read of the week

Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox by Lina Khan

[My heavily annotated copy with highlights and notes] [Original]

During my haircut this week, I talked to my barber about our Kindles, Amazon, and it’s grip on our behaviors. That conversation inspired me to go back to Lina Khan’s Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox – the closest thing that the legal community will have to a viral piece.

Over the course of 96 heavily-footed pages (many of which would make for perfect sub-280 character tweets), Lina presents a comprehensive history of anti-trust law, explains the flaw in our current interpretation of it, shows the reader why Amazon’s conduct is concerning, and outlines a way forward.

Since most readers don’t care for 100 page law articles, and yet the topic fascinates and affects most of us, I thought I’d do the heavy lifting for you and summarize Lina’s positions.

Over the course of reading the piece, I found myself torn between being convinced by Lina’s airtight arguments about why the fact that Amazon has made itself the essential infrastructure for its competitors is troubling and being skeptical of the entire piece due to the obvious benefits to customers. Ultimately, Lina’s policy prescriptions offer us plenty of options no matter where you end up on that spectrum.

Let’s dig into it:

A mini-history of antitrust laws

There are two pillars of antitrust laws that Lina explores – predatory pricing and vertical mergers.

Predatory Pricing: Predatory pricing is defined as “the pricing of goods or services at such a low level that other suppliers cannot compete and are forced to leave the market.”

Current anti-trust doctrine, dominated by the Chicago School, maintains that although this is theoretically possible, it rarely occurs in practice. They argue that firms operating under a profit-maximization framework would never engage in such tactics. And even if it is used as a tactic to drive out competition, the predator would need to recoup their losses over a long enough horizon that it would invite too much competition. The uncertainty of the success of this strategy makes predatory pricing unappealing.

Lina argues that this argument falls apart in the context of online platforms. Often, “below-cost” pricing is rational, since they invite scale and network effects are what make online platforms powerful. Therefore, “reasoning that originated in one context has wound up in jurisprudence applying to totally distinct circumstances, even as the underlying violations differ vastly.”

Vertical Mergers: Vertical mergers is defined as “the combination in one company of two or more stages of production normally operated by separate companies”

Again, the dominant Chicago School doctrine maintains that antitrust concerns from vertical mergers are largely unfounded. They argue that under the profit-maximization framework, if retailers started to favor manufacturers they owner, this would invite competition for the retailer since the other manufacturers would look for a more level playing field in alternatives. Even if it persisted, they argue that any efficiencies found would be passed on to the consumer in the form of lower prices. Their upshot is that any “law against vertical mergers is merely a law against the creation of efficiency.”

Lina argues that this narrow view of customer welfare doesn’t consider the entire structure of an industry. Specifically, vertical mergers increase the barriers to entry across multiple domains and create inevitable conflicts of interest. Unless we agree to be beholden to benevolent dictators, we should scrutinize vertical mergers of online platforms.

With the history of antitrust laws under our belt, we can move to the core criticism of the current antitrust regime.

Focus on outcomes vs. structure

Lina’s overarching critique is that the current antitrust laws focuses too much on outcomes like lower prices versus maintaining a competitive industry structure. It’s based on markets with non-zero marginal costs with weak network effects – the opposite of the dominant companies today. These characteristics make the historic interpretation of predatory pricing and vertical mergers outdated.

She argues for a more structure-oriented approach which looks out for the influence that a company exerts on the whole ecosystem of an industry. She isn’t worried about companies behaving badly, she wants to ensure they never get the opportunity to do so in the first place.

It is worth summarizing why she is particularly concerned about Amazon. According to her, there have been at least three domains in which Amazon has behaved badly.

Amazon’s conduct

These three domains are the pricing of e-books, the establishment of Fulfillment by Amazon, and the spread of AmazonBasics.

E-books: Amazon has frequently locked horns with publishers over e-book publishing. They have a significant first-mover advantage in the space and have solidified that lead through the ecosystem lock-in created by the Kindle. When the Kindle first launched in late 2007, Amazon priced best sellers at $9.99 to create this lock-in. This worked – through 2009, it sold around 90% of all e-books. Publishers were scared by this since most titles cost between $12 to $30. They worried that this would “permanently drive down the price that consumers were willing to pay for all books.” They were handed a lifesaver by Apple’s iBookstore, where they were allowed to price books however they wanted and give Apple a 30% cut. When MacMillan, one of the big publishers, demanded that Amazon adopt a similar pricing structure, Amazon delisted MacMillan’s books. They ultimately brought them back and since other publishers placed similar demands, Amazon’s ability to price e-books at $9.99 became limited. This was critical to a healthy ecosystem since publishers fund up-and-coming authors through the sales of bestsellers. Reduced revenue (and corresponding reduced profits) from bestsellers would have meant that publishers would not have been able to fund new authors – a critical component of a healthy information ecosystem. Although Amazon was thwarted in its attempt, the fact that the information ecosystem had to be saved by Apple is itself a testament to the immense power wielded by platforms.

Fulfillment by Amazon: Independent sellers can use Amazon’s delivery infrastructure to sell their goods. In many cases, this is cheaper than using UPS or Fedex for these sellers. But the UPS and Fedex have increased their pricing for independent sellers in large part due to razor thin margins from their business with Amazon. Amazon also uses UPS and Fedex for its delivery infrastructure but gets more preferable rates due to the volume of its business. As Amazon becomes more dominant, it is in a position to extract more favorable terms with these delivery companies. Since they don’t want to risk the massive volumes of business that Amazon brings, these companies typically comply to these demands. But in order to stay financially successful, they have to compensate for lost revenue from Amazon with increased revenue from independent sellers looking to use their services. This in turn moves more independent sellers to Amazon due to their lower rates. So, in essence, Amazon has inserted itself as a middleman between independent sellers and delivery companies in a self re-enforcing feedback loop. As a result, these independent sellers have to give increasingly larger cuts of their revenue to Amazon. This means less resources for product innovation and expansion – ultimately harming consumers.

AmazonBasics: It’s no secret that Amazon uses data from its marketplace and creates private label versions for popular and profitable products under the AmazonBasics umbrella. While private labels are not a new phenomenon, Lina argues that “the difference with Amazon is the scale and sophistication of the data it collects. Whereas brick-and-mortar stores are generally only able to collect information on actual sales, Amazon tracks what shoppers are searching for but cannot find, as well as which products they repeatedly return to, what they keep in their shopping basket, and what their mouse hovers over on the screen.” A difference in quantity becomes a difference in quality. It sheds typically risks associated with innovating by leveraging its marketplace data and reaps the benefits of it. This limits the ability of firms to innovate because any potential profits are eliminated by Amazon.

Where do we go from here?

There are obvious anti-competitive concerns with internet platforms. So what do we do about them?

Lina suggests two potential options:

Stop them from becoming dominant: If we decide that we should not let online platforms become powerful, we can stop them from ever getting there through regulation.

For Lina, this occurs across the dimensions predatory pricing and vertical mergers.

Predatory pricing laws should expand their scope to include the winner-takes-all effects associated with online platforms which makes it rational to lose money for long periods of time in order to recoup them later.

Vertical mergers should be more strictly scrutinized when exchange of data is involved. For example, the merger of Facebook and Instagram brought together two very large databases of advertisers and user behavior, largely eliminating competition in the social media ad space.

Accept a “natural monopoly” position and regulate them: If we come to the conclusion that we want to keep the benefits associated with the economies of scale of online platforms, then we can regulate them. There are a variety of tools that could be used for this. Nondiscrimination schemes can ensure that Amazon cannot privilege its own goods and limits can be set on the cut that Amazon is allowed to take from its merchants. Regulators can definitely get creative here.

I think this is a topic that will only become more politically heated in the next few years. Reading Lina’s paper is like seeing a vision of the future with all the possible realties. I highly recommend you check it out. Here’s a link to my annotated copy.

Business move of the week

FTC blocking Edgwell’s acquisition of Harry’s

Have you ever wondered how it’s weird that the economic wizards of the Federal Reserve can just create unlimited amounts of money to provide “fiscal stimulus” to the economy? It seems a little odd to me. After all, me and you can’t do that. So why can the Federal Reserve?

David Graeber, in his book Debt: The First 5000 Years, asks the same question and presents an answer:

There’s a reason why the wizard has a such a strange capacity to create many out of nothing. Behind him, there’s a man with a gun.

The man with the gun is the federal government. And this week, the man with the gun – more specifically the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) – reminded us that we are just playing in his backyard by blocking the merger of shaving brand Harry’s and Edgewell.

There’s a few aspects of this that I want to explore – why this happened in an age where every merger seems to go through, the choices it leaves Harry’s with, and how it impacts the future of direct-to-customer brands.

Why did this happen?

In the last decade, every merger seems to get approved. Even ones like Facebook and Instagram, which so obviously made social media advertising a largely monopolistic affair. So why were Harry’s and Edgewell not allowed to merge?

The reason is that anti-trust laws have a good framework for goods with non-zero marginal costs and have not been adapted for the internet age. Most of the “how in the world were they allowed to merge” cases have been internet companies. Harry’s and Edgewell operate in the more traditional CPG industry.

The FTC argues that Harry’s created a competitive environment for razors which led to increased innovation in the space and decreased prices. A merger between Harry’s and Edgwell would eliminate these forces and lead to decreased customer welfare.

Since at the end of the day the man with the gun holds all the cards, what will Harry’s do now?

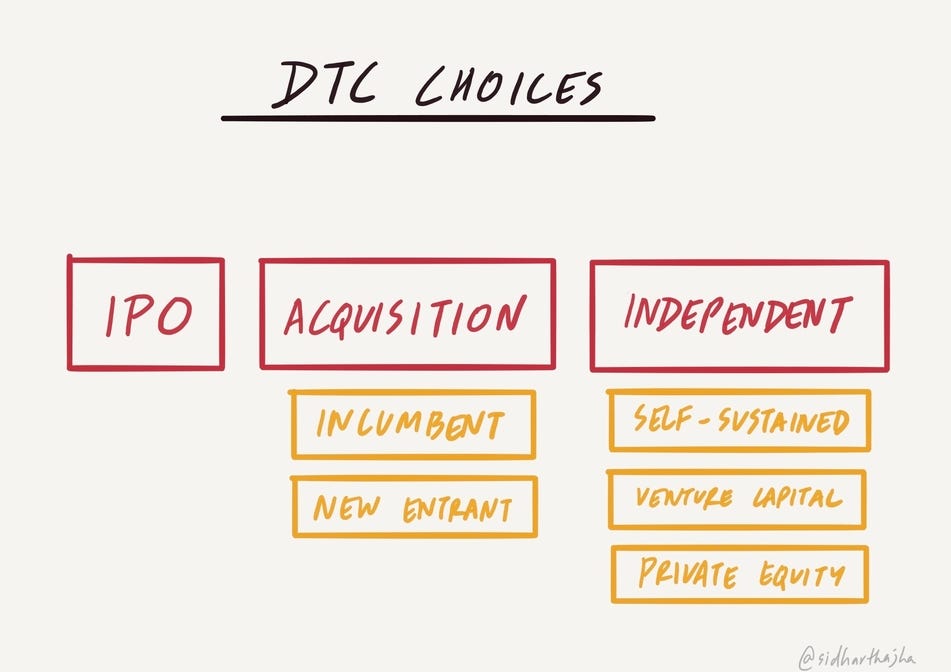

Harry’s choices

Any privately owned direct-to-consumer brand like Harry’s has three buckets of choices:

IPO: You can take your company public by hiring an investment bank, going on a “roadshow”, opening up your books to various institutional investors, and ringing a shiny bell on a chosen date. Both retail and public investors can choose to invest at a given share price and you’ll typically see a “pop” on the first day. Oversimplified, the amount of money that people invest in your company is equal to the difference between the initial and final share price on day 1 multiplied by the number of outstanding shares. Companies these days typically resist this and it’s honestly understandable. You have created a baby and now you have to send it to school where the other kids and teachers might make fun of it. It’s exposed to the vagaries of the market where by no fault of its own, it might experience wild fluctuations in price. It’s also been a tough few months for IPOs. The tsunami of criticism brought on by the botched WeWork offering has left a sour taste in everyone’s mouth. If your financials are not impeccable and you might need a little help before experiencing profitability, this doesn’t seem like a great option – at least not in February 2020.

Get acquired: This is when another company buys your customer. Typically, this will be an incumbent in your industry which feels threatened by you and wants to “buy out the competition” and maybe even achieve some better economies of scale through streamlining the processes of the combined company. This is what Edgewell was trying to do with Harry’s. It can also be a company might be in a complementary industry trying to jumpstart a division. For example, before Apple entered the cloud storage market with iCloud, they considered acquiring Dropbox.

Remain independent and private: The last thing you can do is remain independent and private. You can either do this by being a self-sustaining business, or by attracting private investors in the form of venture capital or private equity. Self-sustaining businesses are great, but in order to scale in a business without software margins is difficult. You have to raise debt or equity. When it comes to venture capitalists, it seems like everybody is one these days. In an age of near-zero interest rates and a stock market boom that doesn’t seem to end, capital is but a commodity. Private equity firms typically raise a blend of equity and debt. They have historically had a bad reputation as ruthless rodeos who are in it for the short-term “turn around” and “flip.” But I think this is exactly what the DTC space might need. Too many companies consider themselves a “tech company” because they have a Shopify account and use a few levels of automation. Private equity investors will come in, cut the fanciful fairy tales and wishful valuations – maybe cut some overhead – and hep build a sustainable and successful business.

The future of DTC brands

In many ways, Harry’s is the poster child of the DTC phenomenon. It attacked a product line with stifled innovation by incumbents (going from 3 to 5 blades hardly counts as innovating) for a large target audience, managed to make a real impact on the industry and gained significant market share.

The future might seem bleak. After all, one of the most lucrative exit avenues just suffered a serious pushback. But it’s important to remember that DTC is still a real channel. Don’t be influenced by short-term narratives. Consider this as you would a momentary drop in the stock price of a company with solid fundamentals.

But never forget whose playground you’re playing in.

Random corner of the week

I came across these gorgeous movie posters by Matt Needle at @needledesign for all the Oscar-nominated movies. The use of color and contrast is striking. Check out more of Matt’s work on his website.

Meal of the week

On my last day in New York City, I went to Ippudo and had the vegetarian ramen. I was pleasantly surprised by it and definitely recommend it. They have a few locations in the city so you can choose the one closest to you.

That wraps up this week’s Sunday Snapshots. If you want to discuss any of the ideas mentioned above or have any books/papers/links you think would be interesting to share on a future edition of Sunday Snapshots, please reach out to me by replying to this email or sending me a direct message on Twitter at @sidharthajha.

Until next Sunday,

Sid