Walmart = Socialist?!, Culture and Clothing, and the $13B Hypocrisy

In which I write about Walmart and Apple

Hey everyone,

Greetings from Washington, D.C.!

Things happened this week. Jeff Bezos stepped down as Amazon’s CEO. The Super Bowl is today. Substack has footnotes now.1

And in news of equal personal importance, Snapshots is now into the nervous nineties - this is the 90th consecutive weekly issue of the newsletter. There are still a couple of months to go, but what would you like to see for the 100th issue? Send me ideas, inspiration, or any random thoughts here.

For now, let’s focus on the this issue in which I want to explore:

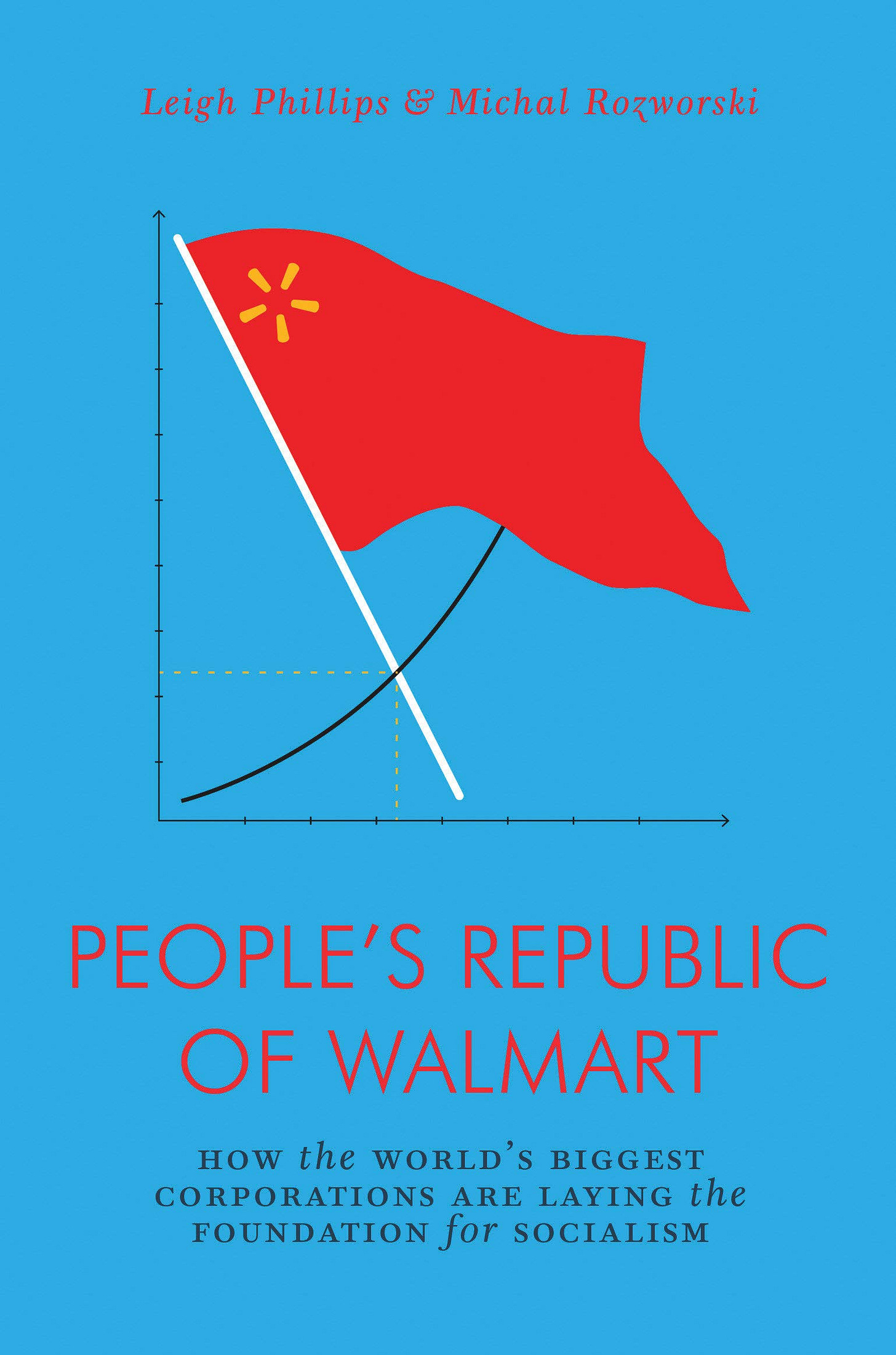

The People’s Republic of Walmart Pt. 1

Using Neural Networks to map culture and clothing

The $13B Hypocrisy

The “Link in Bio” Wars, A rare Patek Philippe, and Cybersecurity Wars

Book of the week

One of the more interesting thought experiments I’ve seen people work through is to take a interpersonal dynamic and see at what scales are those dynamics applicable to. And more importantly, at what scales do they break down.

To make it less abstract, let’s say we’re talking about gift giving and reciprocity. If you’re going to a family member’s birthday party2, you’ll buy them a gift and there is little expectation of reciprocity from them. But if you bring a gift to an acquaintance’s party, the implicit social convention dictates that they have to buy something of equal value for your birthday. What works at the family scale does not work at the acquaintance scale.

Well, this is also true of companies and the heralding of capitalism as the be-all and end-all of companies. Even the investment bank Goldman Sachs, known for its cutthroat practices, acts like a communist community from within as a result of their partnership system of governance.3 Walmart, the supermarket giant is also no stranger to this duality.

In The People’s Republic of Walmart, Leigh Phillips and Michal Rozworksi lay out an argument that describe planned economies by describing them as a natural next step as extensions of the mega-corporations of the today, Walmart included. While the company may compete against other companies in the external market, internally it is extremely cooperative:

Yet while the company operates within the market, internally, as in any other firm, everything is planned. There is no internal market. The different departments, stores, trucks and suppliers do not compete against each other in a market; everything is coordinated. Walmart is not merely a planned economy, but a planned economy on the scale of the USSR smack in the middle of the Cold War. (In 1970, Soviet GDP clocked in at about $800 billion in today’s money, then the second-largest economy in the world; Walmart’s 2017 revenue was $485 billion.)

A corollary to this is that Walmart’s massive scale means that even its suppliers are kind of a part of the company itself. The company sets in place long-term, high-volume partnerships with most of its suppliers and therefore the resulting data transparency and cross-supply chain planning decreases expenditures across the board.

But perhaps most interesting is what happens if you do the opposite of what Walmart does – what Christian theologians call via negativa. In this case, that means asking the following question, “What happens when every department inside a company competes against each other?”

A beginner or intermediate microeconomics class would lay out the theoretical framework of how departments would find out an equilibrium price and quantity for the required resources and all will be good. However, the very practical experience of another giant retailer of the past – The Sears Corporation – indicates otherwise:

And so if the apparel division wanted to use the services of IT or human resources, they had to sign contracts with them, or alternately to use outside contractors if it would improve the financial performance of the unit—regardless of whether it would improve the performance of the company as a whole. Kimes tells the story of how Sears’s widely trusted appliance brand, Kenmore, was divided between the appliance division and the branding division. The former had to pay fees to the latter for any transaction. But selling non-Sears-branded appliances was more profitable to the appliances division, so they began to offer more prominent in-store placement to rivals of Kenmore products, undermining overall profitability. Its in-house tool brand, Craftsman—so ubiquitous an American trademark that it plays a pivotal role in a Neal Stephenson science fiction bestseller, Seveneves, 5,000 years in the future—refused to pay extra royalties to the in-house battery brand DieHard, so they went with an external provider, again indifferent to what this meant for the company’s bottom line as a whole.

Madness!

Clearly companies need to cooperate within themselves, but what does mean for the national economies? Should they be planned as well? Should we lean into the c-word?

Stay tuned for next week’s issue of Snapshots to find out.

Long read of the week

From Culture to Clothing: Discovering the World Events Behind A Century of Fashion Images by Wei-Lin Hsiao and Kristen Grauman

What an amazing research paper about tying fashion styles to their cultural contexts. Most interesting to me is the methodology used to parse together the tasks. It’s basically a series of neural networks that are linked together such that the output of one is the input of the next. This allows each task to be done by an algorithm that is best suited for it. Then you string them together.

I’d be curious to learn how the lack of a “global” algorithm that has A->Z visibility hampers the overall quality of the model. Likely, creating this one-fits-all-tasks algorithm isn’t even possible right now.

The commercial application of an algorithm like this are not too tough to think of. A company like Stitch Fix would love to take or mimic the underlying approach and use it for better personalized recommendations. Amazon could use it to influence better product development for its clothing private labels.

Business move of the week

The $13B Hypocrisy

Once again, Apple and Facebook are fighting about Apple’s upcoming changes to the IDFA (Identifier for Advertisers) tool which will ask users where they want to be “tracked” or not using that terminology. Oh boy do I have issues here.

I am no Facebook apologist. And I do think that users should have better information about how their data is being used. But Apple’s hypocrisy is problematic. And it’s problematic to the tune of 13 billion dollars.

Apple allegedly receives that amount from Google for the latter to be the default search engine on iOS. This is paid out on a pay-as-you-go basis based on the number of searches conducted on iOS devices through Google’s services. Doesn’t Google also use, misuse, or abuse the data in the same way that Facebook does?

So why does Apple not have a problem with Google but is picking a pretty direct fight with Facebook? Well, here’s one explanation from this interview is that Apple wants greater revenues from discovery via the App Store. This includes — drumroll – search ads, amongst other things. Right now, most of this discovery comes through Facebook ads.

I am actually quite sympathetic to accidental power. Often you can do something that’s wrong/illegal just by the virtue of the fact that you are a large company. But there is nothing more dangerous that been powerful and thinking that you are right.

More on this in Matthew Ball’s amazing piece about Apple and evolution of the internet of the future.

Odds and ends of the week

Three article this week:

⌚ An extremely rare Patek Philippe: An appropriate follow-up to the other Patek Philippe piece I wrote about a couple of weeks ago. Super neat.

🔗 The “Link in Bio” Wars: A great and thorough article by Marie Dollé about the link in bio section of various social media platforms.

💻 The cyberweapons war: If you think we’re not at war, think again. A pretty disappointing read about the state of affairs when it comes to defensive and offensive abilities.

I could do an entire issue of Snapshots titled A Love Letter to Footnotes. But I like my subscriber numbers and have no desire to see them drop off a cliff.

Remember those?

Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s Skin in the Game paraphrasing David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5000 Years

That wraps up this week’s newsletter. You can check out the previous issues here.

If you want to discuss any of the ideas mentioned above or have any books/papers/links you think would be interesting to share on a future edition of Sunday Snapshots, please reach out to me by replying to this email or sending me a direct message on Twitter at @sidharthajha.

Until next Sunday,

Sid