Crevices in the Rock

The resiliency and importance of Brick & Mortar stores in today's retail environment

When I first moved to the midwestern United States for college, there were a lot of things that I was unprepared for. I was not prepared for the giant lecture halls. I was not prepared for Daylight Savings Time. I was certainly not prepared for the level of independence I had.

But above all else, I was not prepared for the brutal winters.

During the first of these bone-chilling winters, I noticed a phenomenon which I had never seen before as someone who had spent most of his life within a few latitudes of the Equator.

Outside my freshman dorm on the bank of Lake Michigan was a road. All across this paved road, there were tiny crevices. And in those crevices was water. And while in the always-too-short-lived Fall the water was liquid, as soon the temperatures dropped, it turned into ice. And as soon as it turned into ice, the road started to crack. That entire winter, maintenance crews bundled in neon jackets and yellow hard hats would come to clear out the cracks and crevices of any liquid, but the water would find a way. It would keep cracking up the road which thousands of students walked on every day for the entire season.

The Uptick

There is another road, the road not to moldy and alcohol-laden freshmen dorms, but the road to the future of retail. It’s a road which is not paved with concrete, but is being increasingly paved with the paraphernalia and infrastructure of e-commerce — warehouses, shipment boxes, delivery trucks, and the human and financial machinery that lubricates it all.

COVID-19 certainly did not halt the paving of this road in this manner. In fact, it accelerated it. The now famous “uptick” in e-commerce sales as a percent of total retail sales in the United States in 2020 shows that as we moved towards lockdowns, the road kept being paved.

But just like the crevices in the road in front of my college dorm, there are things that are resilient to disruption. Though they are ignored in the zeitgeist of how the Stripes and Shopifys of the world are changing commerce, brick and mortar stores remain a powerful force.

And nowhere is this more apparent than in the recent IPOs of Warby Parker and AllBirds.

The DTC Darlings

Every one around me who wears prescription glasses has at least considered buying them from Warby Parker. That level of cultural penetration is impressive for a brand that’s only been around for a bit more than a decade. In some ways, Warby Parker is one of the quintessential DTC brands, lagging behind only the likes of Dollar Shave Club and Harry’s. And it did so without any gimmicks. It just took a market effectively monopolized by Luxottica and offered consistent pricing ($95 across all frames), easy-of-use (you could receive multiple pairs in a shipment and send back the ones you didn’t like), and a digital-first approach. That last fact was so rare in 2008 that business school professors and investors across the world were faced with a gluttony of “Warby Parker for X” pitches in the early 2010s.

But in 2013, the company opened its first store in New York. And the retail bug has bitten the company — 85% of their 145 retail stores were opened in the last 5 years and they believe that their “growth strategy contemplates a significant expansion of [their] retail store footprint.”1 Specifically, they plan to open “30 to 35 new retail stores in 2021 and will seek to continue this pace of rollout into the foreseeable future.”

Prior to COVID, their channel mix was 65% to 35% in favor of retail! After a bend towards online sales in 2020, it’s back to a 50-50 mix for the first half of 2021. And these sales are profitable — their “four-wall margins” (which reflects the sales of each store relative to the direct costs required to operate the store such as rent, utilities, wages, etc.) of 35% for an average sales per square foot of $2,900.

As for Allbirds, perhaps the first and only time yours truly will be earlyish to a footwear trend, I remember getting a pair of the original grey shoes in 2016. This was before they became a mainstay of every wardrobe in San Francisco and “tech boy” starter packs. But become mainstay they have. Effectively cornering the ~$100 price point for large swaths of urban customers, they have used this perch to launch new initiatives in the apparel category. But despite the delightful turn-open packaging that’s clearly designed with shipping in mind, retail remains an important part of their strategy. They opened their first retail store in San Francisco in 2017 and every time I happen to be in front of their Georgetown location in DC or their SoHo location in NYC, they are full of customers. The numbers back up that anecdote — they have 27 stores across the country which drive 11% of their revenue in 2020. This number was 17% in the ancient days of 2019.

But more importantly — and interestingly — Allbirds goes into the numbers of how the retail and online channels interact with each other. They note that “in the three months after [their] Boston Back Bay store opened in March 2019, the Boston DMA region saw a 15% increase in website traffic, and 83% increase in new customers, and ultimately, a 77% increase in overall net sales, as compared to a comparable control market.” Those are very impressive numbers! Zooming into the customer level, multi-channel repeat customers represent 12% of their total repeat customers and on average spend ~1.5x more than their single-channel repeat customers.

So what’s happening? How did these digitally-native DTC darlings turn into brick and mortar geniuses? And what lessons can investors and other companies learn from this?

Shades of LTV:CAC

If there is one equation that executives learn to live by, it’s the ratio of lifetime value to customer acquisition cost or LTV:CAC. The ratio answers the simple question of “is the money you are spending on acquiring customers worth the money they will spend on your products and services?”

And while it is technically correct that you always want the alligator to be eating the LTV side of the inequality2, a single number can hide a lot of nuance. In the case of companies like Warby Parker or Allbirds, it hides a lot of nuance between the stages of growth a company goes through.

Ideally, as a company get larger, things become more efficient on both sides of the ratio. You have greater brand awareness so your acquisition costs go down and your lifetime time goes up by a combination of expanding products and lower costs due to volume pricing power for your inputs.

But that ideal scenario rarely happens. In fact, often the exact opposite happens, even to the best companies. As Nathan Baschez and I wrote in Complexity Convection:

Businesses are born simple. They attract early cohorts of users with equally simple needs. Then, as users get the hang of things, their needs become more sophisticated. So the business listens to its customers and adds complexity into the product. It’s a co-evolutionary process, where everybody is optimizing according to their knowledge and incentives.

And what is true for businesses in general is also true for marketing specifically. Initially, a company attracts customers whose needs they perfectly serve. You need to spend little to no money to convince them to use your products. But after this low-hanging cohort of perfect customers is captured, things get a bit tough. You have to convince customers for whom the product is not perfect, but pretty good. Once you have exhausted that cohort, you go on to the next one and so on.

In reality, for the same product, on average you are going after will require more money to acquire and their lifetime value will be lower.

As a CEO/COO/CMO, what levers do you have to pull out of this spiral? You can change the pricing of the product, implement more efficient ways to advertise the product, etc. But one of the most powerful levers you have is the distribution channel.

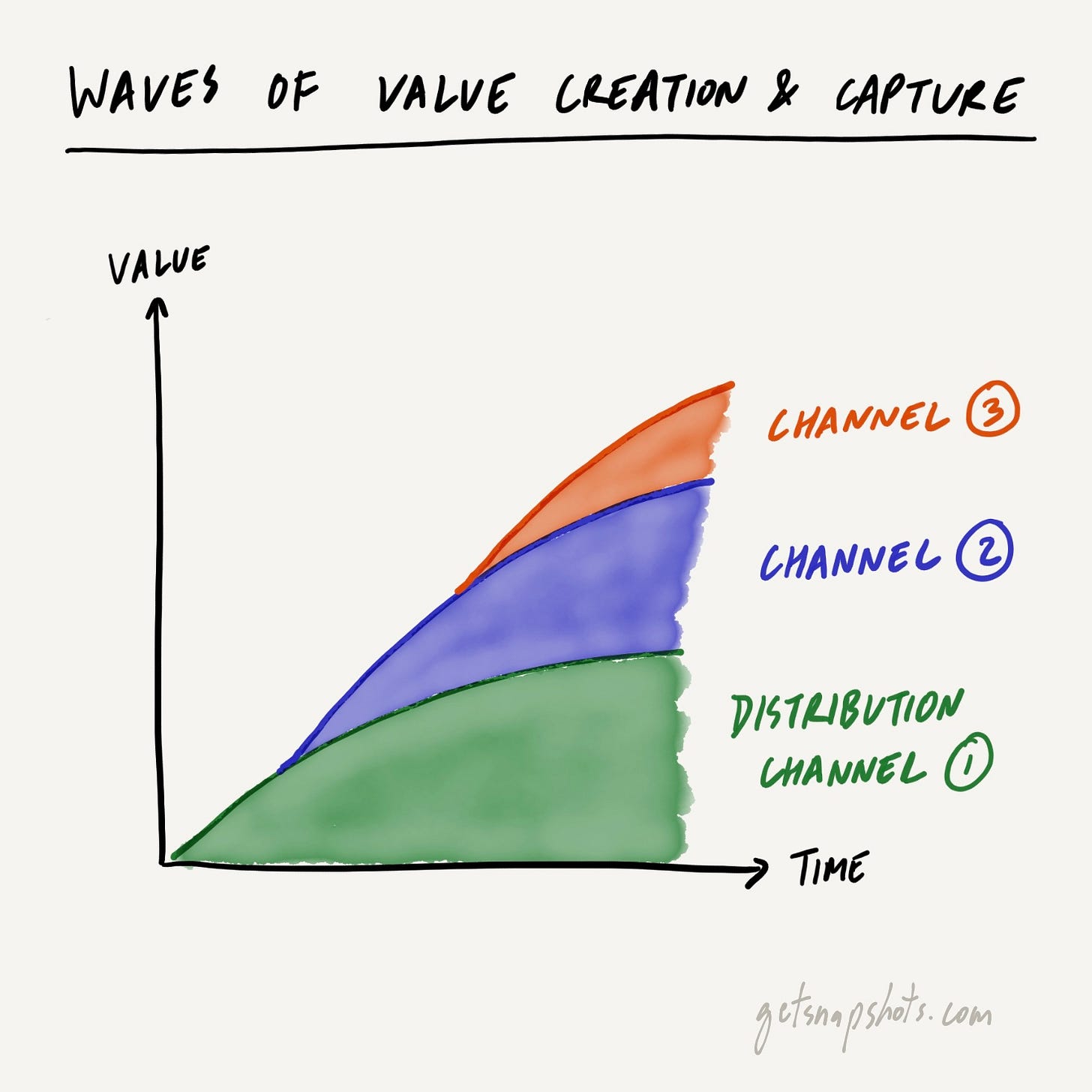

Based on what we’ve talked about, the curves for a specific distribution channel over time look something like this:

Let’s say this distribution channel was social media platforms. While things looked great in the beginning when you had just started by attracting the highest affinity customers to your products, you’ve now run out of customers in that cohort. You’ve been pouring money into Facebook and Google ads with barely any bumps. Things look dire. But you can change the story by choosing a distribution channel.

When you get into a new distribution channel (and start again at t=0 in the diagram above), you get the benefits of customers who were potentially never exposed to your previous distribution channel. It’s a lot like a new school, a new job, or a new relationship — you get to start at square one. Yes, you have the baggage and benefits of your existing brand, but you’ve tapped into a new vein of potential customers.

That’s exactly the purpose that retail stores serve for Warby Parker and Allbirds.

Here’s what Warby Parker have to say about the value of their stores:

Our retail stores serve as valuable marketing vehicles for introducing new customers to our brand and driving repeat purchases and, in turn, positively impact our Sales Retention Rate. Customers are drawn to the vibrant appeal of our retail storefronts and the distinctive in-store experience. We have designed our stores to be convenient, fun, and inspirational — and pride ourselves on the service our teams provide.

Note that they highlight stores as a marketing channel first and as a sales channel second.

Allbirds says more or less the same:

Our stores serve as an effective and profitable source of new customer acquisition, increase awareness of our brand, and drive traffic to our digital platform.

After you’ve been accustomed to declining ROI on your marketing, this can feel a bit like cheating. And yes, it’s a different set of competencies — running a story on Bond Street is very different from running a Shopify story from a basement. But it’s a necessary set of competencies to develop if you want your company to not just grow, but to grow up.

At the end of the day, you want to increase the value that you are creating and capturing. To do so, you need successive ways of new distribution channels.

Every distribution channel will plateau in growth, and you’ll have to continuously find new ways to acquire the marginal customer. That’s the nature of the beast.

If you like this essay, consider subscribing to the newsletter to get the next one directly in your inbox:

Bullet and Bandages

It is true that what works for Warby Parker and Allbirds does not necessary work for every DTC brand. In fact, it can be pretty tough to tell if a new product will be successful or not — every social media feed is filled with a deluge of pastel-colored goodness.

It is also true that retail is a bit more zero-sum in a way that is not true for e-commerce. There are only so many stores in a particular area compared to the endless scrolling of e-commerce that is just a few taps away.

So if I were a public or private market investor, instead of trying to pick the next Warby Parker or Allbirds, what makes a lot more sense to pick is the infrastructure and tools that will power the next wave of Warby Parkers and Allbirds. Instead of betting on someone to win the war, just buy the bullets and bandages.

There are a few opportunities that I see in this space:

Powering the next big thing: How can you make the process of setting up and managing a retail store as much of a turnkey solution as possible? What are the complexities that you can manage to make the retail experience for new DTC brands as easy as possible so that they can focus on their core competencies? There are several players in this category, but the one that sticks out to me is Leap Retail. They provide a two-sided marketplace of brands and landlords to find and manage retail stores of brands such as Rent the Runway, Birdies, Naadam, Koio, Faherty, and many more. Companies like Leap will start off by making money on the marketplace matching services and then have the opportunity to “ladder up” to payment processing, inventory management, and other such services.

Serving the mom and pop shops: On the lower end of spectrum is an opportunity to power the mom and pop stores. The most compelling player in this space is Square with its unique combination of physical POS terminals and the Cash app. I recently went to a coffee shop in DC and noticed a “Save 10% with Cash App” option at a Square POS terminal.

That’s just one example of the type of strong end-to-end integration that Square can enable for retailers. Since its founding days, Square has done an incredible job of managing the complexity needed to accept payments at physical retail stores and its integration with the Cash app on the consumer side makes it a compelling choice for mom-and-pop shops and SMEs looking to get started.

Storefront inventory marketplaces: There is also another way to look at marketplaces — instead of a marketplace for the entire store location, what if you had a two-sided marketplace of brand-agnostic retail locations with available storefront inventory and brands willing to pay to feature their products at these locations. Chicago-based Showdrop offers exactly this functionality. It offers a compelling option for companies not quite ready to make the big jump to a full-fledged store yet but are ready to tap into the growth available in the brick-and-mortar channel.

Incumbent accelerator programs: While not exactly providing infrastructure, programs like Target Accelators can lead to a high magnitude change in a company’s trajectory and hence warrant a mention here. At the end of an arduous application progress is a very big carrot — potential access to shelf placement in Target’s highly lucrative 1,900+ stores across the United States. For Target, the program allows them to pick the best up-and-coming brands as their inventory. Other large retailers like Walmart likely have or will soon have similar programs.

Do the opposite: With every positioning comes a counter-positioning. If there is money to be made in helping the next wave of DTC companies figure out how to do retail, there is money to made in helping the existing set of large retail giants figure out how to do e-commerce. The best example of this which I have seen is Narvar — an end-to-end solution which powers the post-checkout experience — think order emails, shipping reminders, returns, etc. — for companies like Lululemon and Patagonia.

If you’re an investor or a company in this space, I would love to talk and get your feedback on the piece. Please reply to this email or send me a message on Twitter.

Seasons

As the winter receded on the banks of Lake Michigan, the roads got a respite from the constant cracking. And just like the seasons, cycles of attention will come and go. But the crevices will remain.

The digital infrastructure available to an entrepreneur today enables anyone to get started with just an idea. Potential customers are jump a click away. But they are a click away for you, they are also a click away for your competitors. Your access to them through digital distribution channels is unlikely to be differentiated or defensible.

On the opposite side, while it may seem like brick and mortar stores are dying, their zero-sumness has in-built defensibility. And as long as companies need to grow up to become larger versions of themselves in search for the next best customer, physical storefronts will continue to be an attractive channel for acquiring those next best customers.

So the crevices will endure and, dare I say, thrive.

All numbers and quotes in this essay are, unless otherwise noted, from the Warby Parker and Allbirds S-1s

I’m pretty sure that even rocket scientists at NASA have to use the “alligator wants to eat the larger number” heuristic and nothing will convince me otherwise