Spotify Un(wrapped)

Lessons on evolving business models, format hype, and product focus

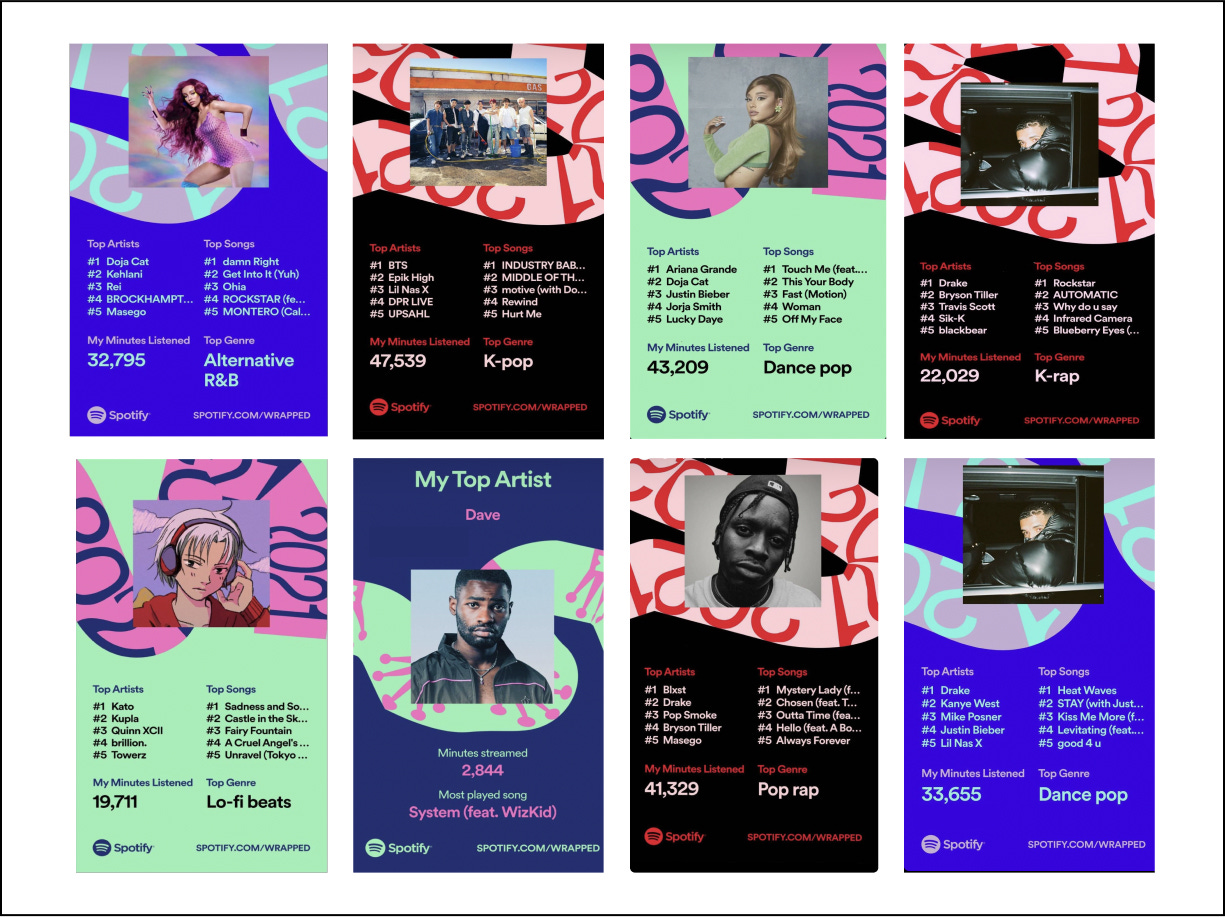

In what has become an annual tradition, Spotify wrapped1 the internet in pastel and fluorescent hues.

But companies — at least companies the size of Spotify — don’t do things just for fun. So what’s the point of Spotify Wrapped? And what can it tell us about Spotify’s business strategy? And are there broader lessons to be learned from this specific format of app engagement?

Spotify’s changing business model

There are two questions that every company has to answer:

How do they make money?

How do they grow?

For Spotify, the first question has historically been fairly straight forward. They make their money from users paying a subscription fee. This fee is $9.99/month for an individual plan in the US; international and group plan prices vary. The latest premium subscriber number stands at 172 million, which is up 19% from 144 million at the time last year2.

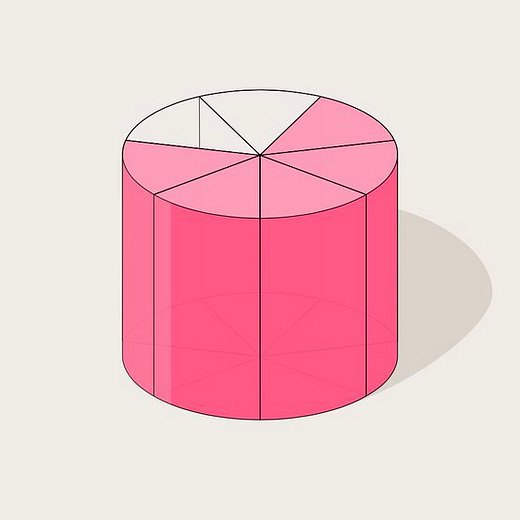

But that is not the only way they make money. They have an emerging business model that is ad-supported. In 2020, the ad-supported business comprised of 9.4% of top-line revenue. In 2021, this number was 12.9%.

And while that alone does not show that Spotify is committed to the ads model, their investments in podcasting do. It’s no secret that Spotify has been buying exclusive content — The Ringer, Gimlet Media, and of course, The Joe Rogan Experience have all been acquired by Spotify over the last couple of years. Building user profiles for targeted advertising is significantly easier with these podcasts which have specific subject matter and preexisting customer segments. This makes the platform more attractive to advertisers who have been working with these podcasts since they were independent. And of course, it also brings in hardcore podcasting fans into the Spotify universe.

In short, the composition of revenue is trending towards ads and Spotify is making significant investments in this segment.

Fast-forward the clock a few years and imagine that Spotify was an American company (alas it’s Swedish) and its CEO Daniel Elk was hauled in front of the US Senate. One of these Senators would ask an unintelligent question about Spotify’s evolving business model. Elk would pause for a second and take in the question. Maybe he would consult with his lawyers. And then he would say, “Senator, we run ads.”

If you like this essay, consider subscribing to the newsletter to get the next one directly in your inbox:

As for its growth strategy, most of Spotify’s growth comes from the two trial-period promotions it runs every year and generic brand/direct response advertising. This is in addition to any natural word-of-mouth. This is all well and good, but growth channels have asymptotes. From Crevices in the Rock:

Initially, a company attracts customers whose needs they perfectly serve. You need to spend little to no money to convince them to use your products. But after this low-hanging cohort of perfect customers is captured, things get a bit tough. You have to convince customers for whom the product is not perfect, but pretty good. Once you have exhausted that cohort, you go on to the next one and so on.

In reality, for the same product, on average you are going after will require more money to acquire and their lifetime value will be lower.

As a CEO/COO/CMO, what levers do you have to pull out of this spiral? You can change the pricing of the product, implement more efficient ways to advertise the product, etc. But one of the most powerful levers you have is the distribution channel.

Based on what we’ve talked about, the curves for a specific distribution channel over time look something like this:

Let’s say this distribution channel was social media platforms. While things looked great in the beginning when you had just started by attracting the highest affinity customers to your products, you’ve now run out of customers in that cohort. You’ve been pouring money into Facebook and Google ads with barely any bumps. Things look dire. But you can change the story by choosing a distribution channel.

When you get into a new distribution channel (and start again at t=0 in the diagram above), you get the benefits of customers who were potentially never exposed to your previous distribution channel. It’s a lot like a new school, a new job, or a new relationship — you get to start at square one. Yes, you have the baggage and benefits of your existing brand, but you’ve tapped into a new vein of potential customers.

The marketing channels of trials and traditional advertising have been firing on all cylinders since 2006 and are bound to go on the wrong side of the LTV: CAC ratio line soon for many cohorts (if not already there). So where do they go?

If we think more about the product that Spotify is selling — audio — at its heart, is a social product. But Spotify, at its heart, is not a social app.

Here’s where Spotify Wrapped comes in.

Spotify Wrapped has been a concept since 2013, but it really took off in 2019 when it became an in-app experience. Critical to this change was the option to easily share your personal music journey to other truly social platforms like Instagram and Twitter3. While there are no concrete numbers around the increase in subscribers that can be directly attributable to the format, it’s safe to say that it’s a number that is significantly greater than zero.

So we understand why Spotify invests in Spotify Wrapped — it’s a way to reach potential users which it may not have been able to reach otherwise through its usual marketing channels. And we understand how it it relates to their evolving business model — more users means more ads means greater negotiating power with advertisers means higher revenue and profits per user.

But what else can we learn from this unique format of in-app engagement?

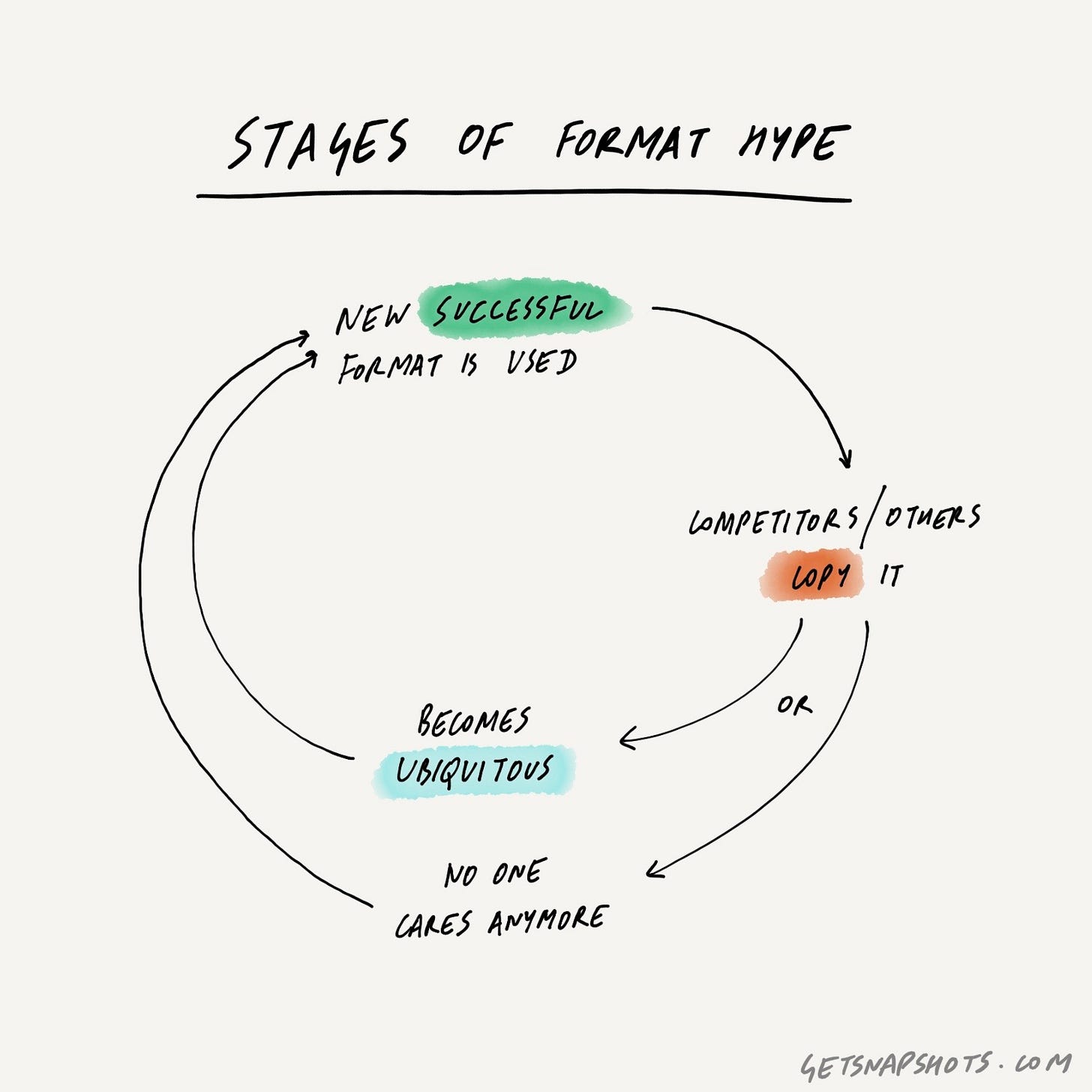

Stages of format hype

With any interesting format, there are other companies which will “take inspiration” from it.

Robinhood and Strava are two companies that caught my eye last year:

The cycle looks something like this:

Something new and novel comes along with the first mover capturing a lot of value.

Others try to copy it. Some capture it successfully and some not so successfully.

The format either becomes ubiquitous or no one really cares about it anymore.

Formats remain novel for only a limited period of time. YouTube’s yearly “Rewind” videos were extremely popular, until 2018 when it became the most disliked video on the platform. If you squint your eyes a little bit, you can see this happening with Spotify Wrapped, with its cringe-inducing TikTok references this year.

Format fatigue is also a real thing. This happened with waitlists for new software after the ultra-premium email app Superhuman had a waitlist of 180K users. In 2019 and 2020, there were many apps with similar waitlists. While applicable for some, these mostly annoyed users and now waitlists are not as common.

All in all, if you want to hop on a format bandwagon, there is a limited window of opportunity for you to do so.

The bandwagon criterion

When deciding on whether or not to follow a new format trend, founders and executives have rely on the honest answer to the question: Does it give you a true edge over acquiring, retaining, or charging customers more?

Otherwise, it’s just a distraction and you’re better off focusing efforts on your core product. For many of the companies who will be trying to copy the success of Spotify Wrapped this December, I suspect the answer is the latter.

What do you think about Spotify Wrapped? Let me know by replying to this email or sending me a message on Twitter.

One of my bucket list items for Snapshots has been to include a pun in the first sentence of an issue. Mission accomplished.

These numbers are from Spotify’s Q3 2021 financial statements, ending on 30th September, 2021.

On a side note, I find it interesting that users willingly share how much data is collected on their moods and tastes over a course of a year just because it’s packaged in a neat and fun format. It goes to show how much positioning can matter and sheds a light on how PR teams have dropped the bag at other tech firms.