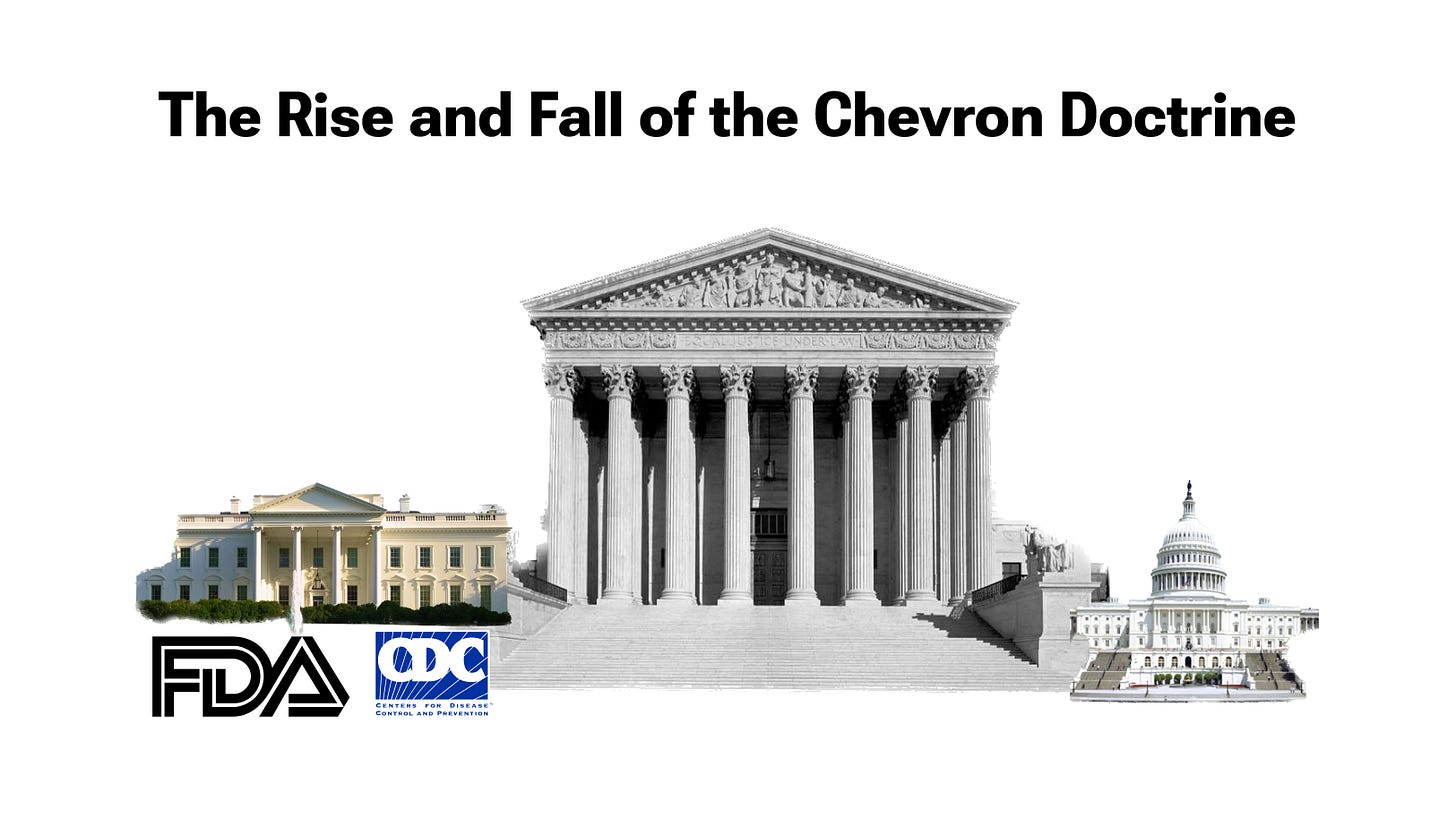

Who Watches the Watchmen

The rise and fall of the Chevron Doctrine

The year is 1984. Apple is running Super Bowl ads about the first Mac computer. Los Angeles is hosting the Olympics. Tetris had just launched on IBM PCs. And discreetly tucked behind the Capitol building in Washington, D.C., the Supreme Court1 is delegating unprecedented levels of legal authority to unelected bureaucrats in the executive branch of the U.S. government.

This is the story of the legal cannon known as the Chevron Doctrine. It says that when a law about an executive agency that has been written and passed by Congress is unclear, the agency’s interpretation is given deference.

And while that may seem benign, dig a bit deeper and it reveals fundamental tensions between the United States’ three branches of government and a deep dynamism in the power structures of a country’s governmental system widely perceived to be stagnant. We find that more power can be delegated away from the ballot box of democracy with an off-the-cuff legal phrase than with formal declarations of authority. Ultimately, this benign technicality shows us the very fabric of laws that govern daily life.

In doing so, we find ourselves face-to-face with some pretty fundamental questions that have always plagued active citizens of conscious republics — what should and shouldn’t be delegated to people who are unelected? How do we maintain a system of government based on checks and balances while individual parts of the system go through turbulent periods? And how can the themes of this story help us in our personal lives?

Let’s dig in, starting with the basic question: what does an executive agency do?

Back to AP Gov: The Basics of US Government

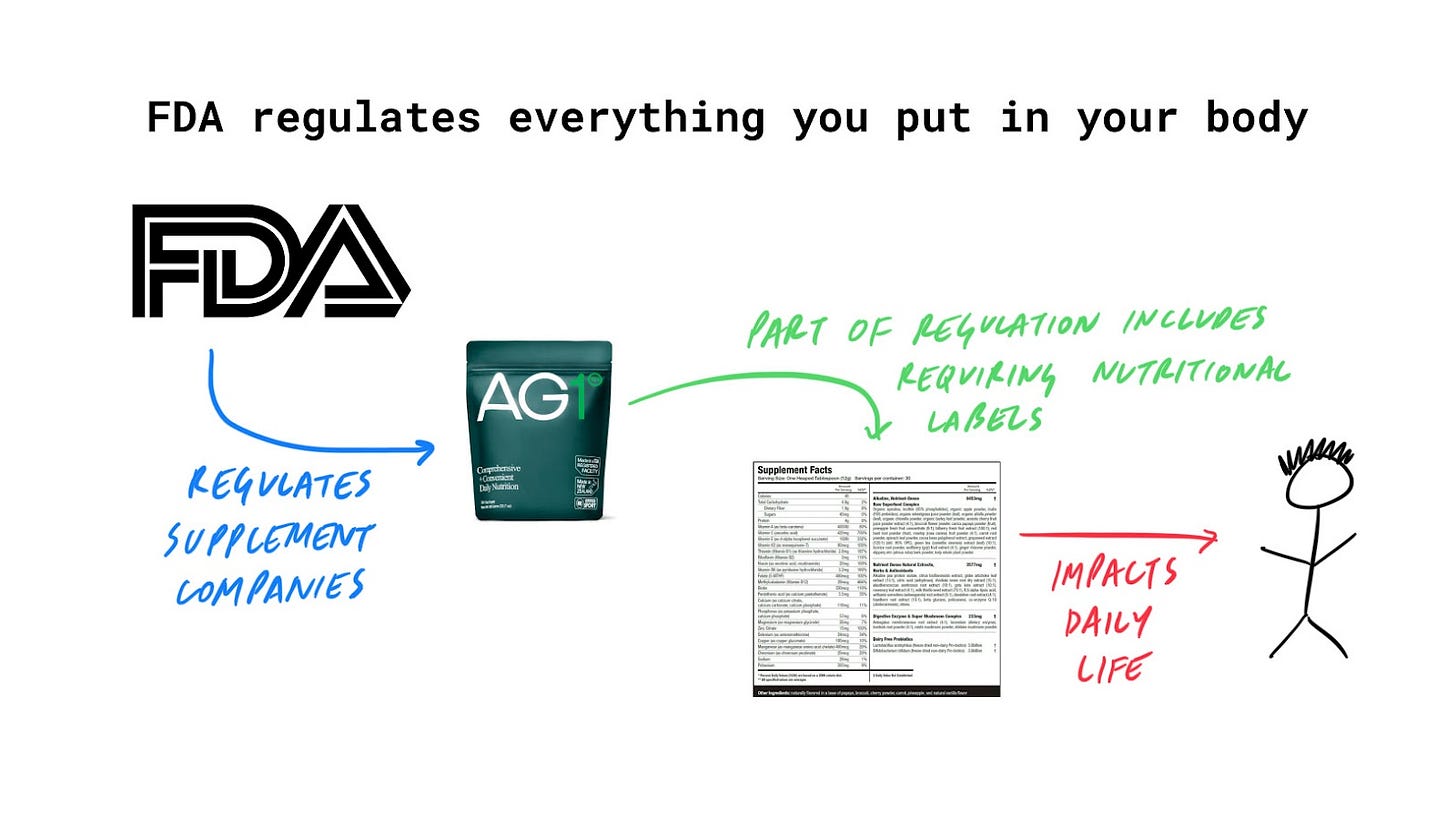

Let's say you go to a doctor and they tell you that you are deficient in iron. You go to a pharmacy or supermarket and pick up an iron supplement from the shelf. On the back of that supplement bottle, there is a nutritional label of facts — a black and white table with a list of ingredients that the supplement is made of and how much of it is in the tablet you're planning on ingesting.

In the United States, companies who sell those bottles are subject to labeling requirements created by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)2. It’s the executive agency in charge of regulating food and drugs; the watchmen in charge making sure that pretty much everything you put in your body is safe. It’s understandably important stuff, and likely more impactful to your life than dull grandstanding on C-Span.

But in the Constitution of the United States, the Food and Drug Administration isn’t mentioned anywhere — so how can it tell companies what's legal and what's not?

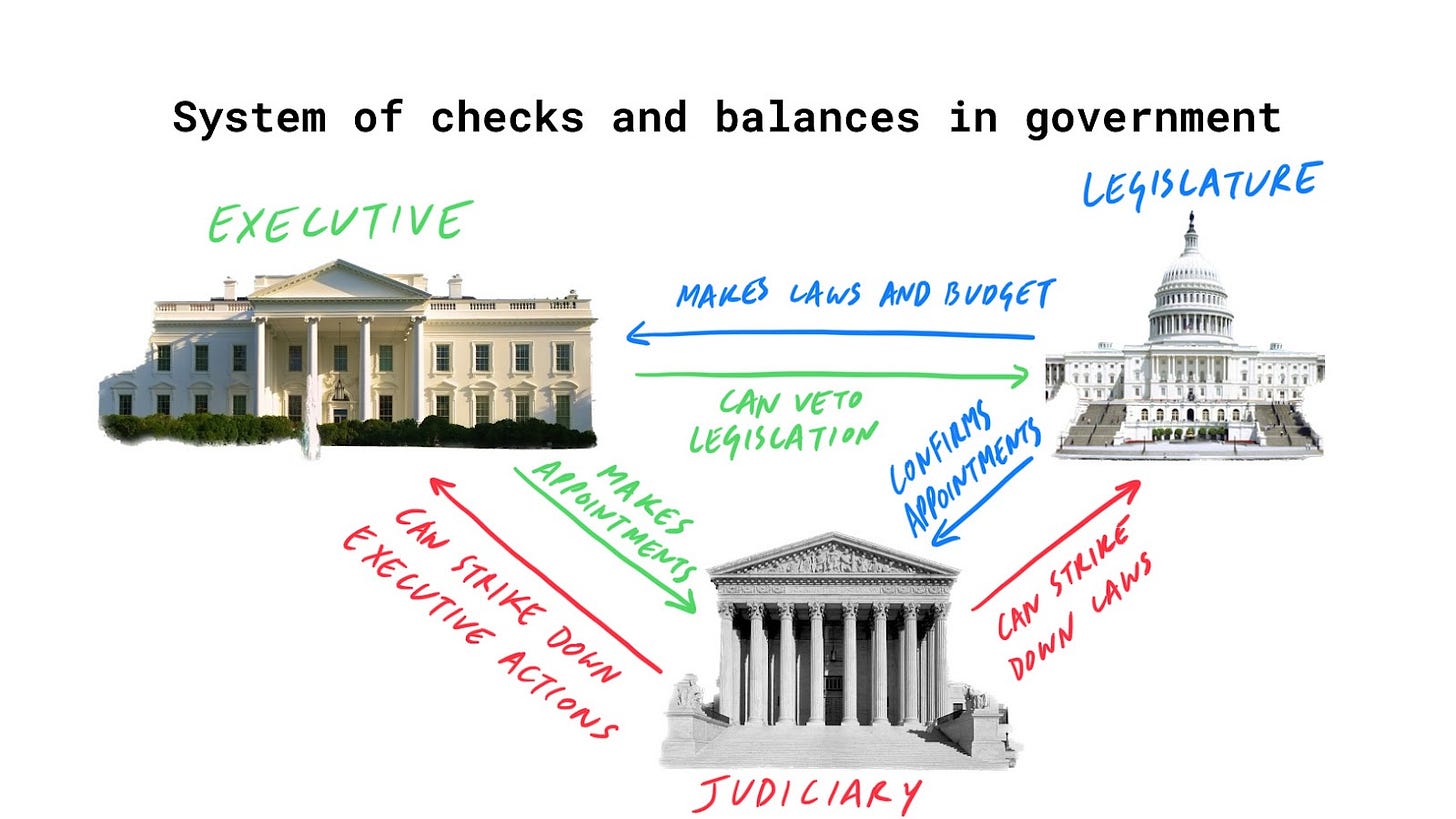

If you went to high school in the United States3, you might have taken an Advanced Placement (AP) Government class in which students learn that Congress — and only Congress — has the power to create laws that govern the land. The President4 is supposed to execute those laws. The Court gets to review these laws (and strike them down if they are unconstitutional5) and make sure that they are being implemented in the way intended by Congress.

In the United States, this system is lauded, because of the checks and balances it theoretically imposes on the powers of the three parts of the government: the Executive (read: Presidency), the Legislature (read: Congress, both the House and the Senate6), and the Judiciary (read: the Supreme Court and all other lower courts).

The various agencies like the FDA, EPA, CDC, etc. are technically under the Executive Branch. They don't have any inherent power. To do anything, like asking power plants to follow carbon dioxide emissions standards, the agency has to point to a law passed by Congress. In this case, the EPA can point to the Clean Air Act of 1963 and this particular section:

(A) The Administrator shall, within 90 days after December 31, 1970, publish (and from time to time thereafter shall revise) a list of categories of stationary sources. He shall include a category of sources in such a list if in his judgment it causes, or contributes significantly to, air pollution which may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare.

(B) Within one year after the inclusion of a category of stationary sources in a list under subparagraph (A), the Administrator shall publish proposed regulations, establishing Federal standards of performance for new sources within such a category.

So, by pointing to (A) the Administrator (the EPA) can say that a power plant is a “stationary source” of air pollution, and by pointing to (B) it can say that it has the authority to assign it a “standard of performance” that it must match.

Every agency has a similar law or set of laws passed by Congress that defines the scope of their actions. The EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) has the Clean Air Act, the SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission) has the Securities Act, the FDA (the Food and Drug Administration) has the Public Health Service Act, and so on and so forth.

All well and good?

Maybe not.

You'll notice the date on the Clean Air Act passed by Congress — 1963 — is over 50 years old as of the writing of this piece. It would be reasonable to ask if the Act is relevant anymore.

You won’t be the first to ask that question. In fact, this question of whether laws can keep up with the on-the-ground realities has been asked since the founding of the country. In one of the Federalist Papers7, James Madison wrote:

All new laws, though penned with the greatest technical skill, and passed on the fullest and most mature deliberation, are considered as more or less obscure and equivocal, until their meaning be liquidated and ascertained by a series of particular discussion and adjudications. Besides the obscurity arising from the complexity of objects, and the imperfection of the human faculties, the medium through which the conceptions of men are conveyed to each other, adds a fresh embarrassment. The use of words is to express ideas. Perspicuity therefore requires not that ideas should be distinctly formed, but that they should be expressed by words distinctly and exclusively appropriated to them. But no language is so copious as to supply words and phrases for every complex idea, or so correct as not to include many equivocally denoting different ideas.

Madison is basically saying: “Hey, I get that not every law is going to be perfectly written by Congress. But you’ve got to do your best and then let things play out between the various parts of the government to figure out what it actually means.”

And at least in this case, Congress is as wise as James Madison. It has also anticipated this question. In cases where it understands that technology might outstrip its ability to pass specific legislation, it writes the law in such a way that it outlines the intended ends, but not the specific means.

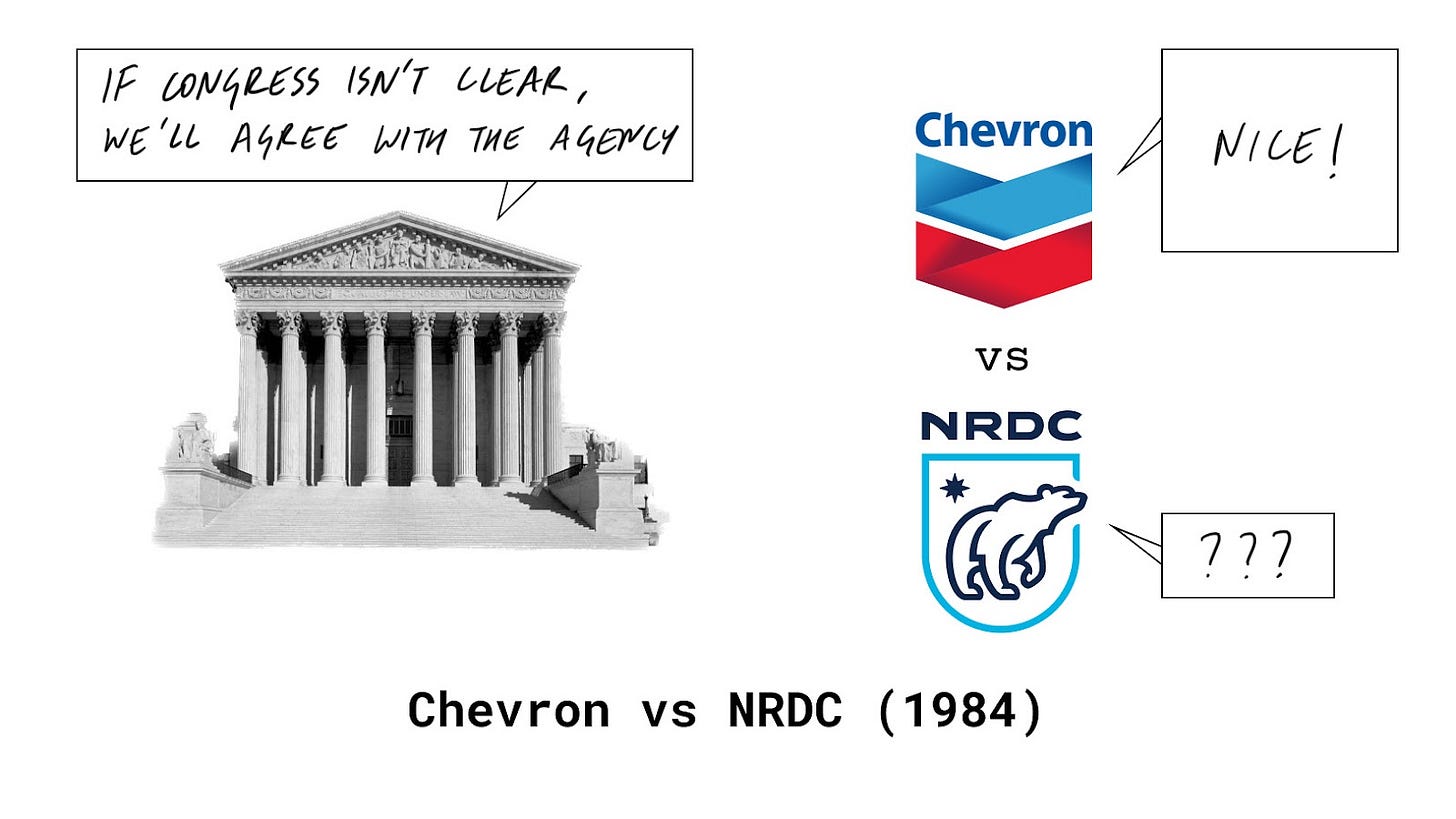

That’s exactly what happened in 1981, when the EPA changed its interpretation of what a “source” of air pollution is to exclude any new equipment for a power plant as long as the emissions from the power plant itself did not increase. Previously, every individual piece of equipment’s polluting potential had to be accounted for on its own. Now, the EPA said something along the lines of, “You have to make sure that the power plant itself does not make more than X units of air pollution. But if you buy a new truck that makes your total emission go over X units, that’s totally fine.”8

Note that while this is not a desirable conclusion if you want to minimize air pollution, there is nothing in the Clean Air Act of 1963 that says that this is not an argument that can’t be made — the law is not explicit about how to deal with these extensions of sources of air pollution.

An environmental advocacy group, the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), challenged the EPA’s novel interpretation of the law. Lower federal courts agreed with the NRDC and concluded the EPA could not change definitions of words used in an act of Congress on a whim.

At this point, Chevron, one of the energy companies that would be negatively affected by this ruling, appealed the decision, and it went all the way up to the Supreme Court.

So, you get the case Chevron vs. NRDC.

When it got to the Supreme Court, the case ruled that the EPA can, indeed, change the legal definition on a whim. Deferring to the agency’s relative expertise (regulating sources of pollution), the case said that agencies should have the authority to interpret ambiguous laws passed by Congress as long as the interpretation is reasonable.

More precisely, it said the following:

First, always, is the question whether Congress has directly spoken to the precise question at issue. If the intent of Congress is clear, that is the end of the matter; for the court, as well as the agency, must give effect to the unambiguously expressed intent of Congress.

If, however, the court determines Congress has not directly addressed the precise question at issue, the court does not simply impose its own construction on the statute . . . Rather, if the statute is silent or ambiguous with respect to the specific issue, the question for the court is whether the agency's answer is based on a permissible construction of the statute.

This becomes known as the Chevron two-step test:

First, the court asks whether Congress has spoken to the exact issue at hand.

If it hasn’t, then as long as two reasonable people can disagree on what the law says and one of the two people is the agency in charge of executing on the law, what the agency says goes.

It’s saying that when things are unclear, the agency has the authority to interpret the law.

The Rise of the Chevron Doctrine

If you squint a little here, you can see how this interpretative power is the end of a very large legal wedge. And it’s a wedge with all sorts of legal entitlements and authority for federal agencies like the EPA, the CDC, the FDA, etc.

Now, you may say, “This sounds good. The agency has more expertise in a particular area relative to the court. Why mess with this and limit the agency’s authority to adjust and interpret the law in order to achieve its regulatory goals?”

There are three reasons why this discretion is concerning:

A regulatory body like the CDC, the EPA, or the FDA might be captured by commercial interests that they are meant to regulate. An entirely separate conversation can and should happen about the fact that 46% of the FDA’s funding in 2021 came from “user industry fees” — a phrase that should be used as an example in the dictionary under the word euphemistic — which means from the companies and industries the FDA is meant to regulate. Sometimes it is offensive to have to point to a legal statute to show that something is wrong; this is one such case. But subtler captures also happen, and it can be tough to discern the ripples on a still pond created by perverse agents lurking beneath in the quiet, murky depths of the administrative state.

Another such subtle capture happens through the revolving door of personnel going back and forth from the regulatory bodies and the industries they are meant to regulate. It’s entirely legal, and while some generous arguments could be made for “cleaning up from the inside”, it’s generally a way for companies to find convenient ways around regulation. In the context of Chevron, this implies having a precise idea of how aggressively the agency you previously worked at would be willing to implement particular laws that your current employer wants to skirt.

Federal agencies are arms of the executive branch. By deferring to the agency in cases of legal ambiguity, you’re giving the President a lot more legal authority than what is prescribed in the Constitution9. That might be fine while your guy or girl is in office, but do you really want to have created this legal entitlement when someone else occupies 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue?10

The Courts are an important bulwark against Presidential and executive overreach. For the Court to delegate interpretative responsibility to nameless bureaucrats at three-letter agencies is broadly undemocratic and against the system of checks and balances as described by the Constitution.

Congress can always make things clearer. But there are two important structural reasons why this is impractical. One, Congress cannot reasonably be expected to be an expert in every single issue and always be prescriptive in its regulation. The agencies will always know more about their own domains. Second, there are times where Congress is extremely divided and is not as productive in getting things done. That’s a natural feature11 of the democratic process.

But it feels weird to give agencies the legal equivalent of a blank check (or at least a check with a very large withdrawal limit) when it comes to interpreting vague laws. These agencies are not staffed with elected officials. Laws, under this deferential system, could be made (via interpretation) by people who are appointed by the President, throwing the system of checks and balances in disarray with huge ramifications for the American people.

Reversal: In Chevron’s favor

A sound rebuttal to this argument would be some series of points like this:

As discussed above, neither the President (elected directly by the people) nor Congress (also elected directly by the people) can speak to every single issue at hand. So necessarily, either agencies or the courts have to interpret the law when it is unclear.

Federal agencies have many constraints on their overall power: their purses are controlled by Congress, their senior leaders are appointed by the President, and any regulatory decisions with higher than $100M in compliance costs must be reviewed by OIRA12, which sits within the President’s office.

Comparatively, Courts are much less accountable. In many cases, the Supreme Court composition is determined by flukes of history. They are somewhat susceptible to an expansion of seats and a tightening of purse strings by Congress, but they can’t really enforce anything they do by themselves13. But many of these limitations are theoretical in nature, and invoking them seriously would lead to a significant escalation in the game of Constitutional hardball that has been played in the 21st century.

All these are fair arguments in favor of broad agency power but they are matters of practicality, not of principle. When we think of solutions to tough problems requiring a balance of trade offs, we have to be cognizant of the edge cases of how systems can be exploited and abused and corrupted — especially a system as powerful and potentially pervasive as the government. No matter how effective and well-meaning they might be, you don’t give institutions with their own agendas loaded guns and ask them to just be nice.

Ends and Means

Note that at this point, it's important to have a more philosophical discussion about distinguishing between an action itself and the authority of an agency to take that action.

How you feel about Chevron at least partially depends on to what extent you feel like ends justify means.

For example, you might agree with an action where the EPA forces every student in America to study climate science in high school. That might even be a socially desirable thing to do. But it doesn't have the authority to do that. It can't point to anything in The Clean Air Act or any other laws that says that this is in their purview.

So even if an action is desirable, it's not necessarily legal.

Should that not be the case? Should agencies be able to look past the law and do what they believe is best for the people?

It can be easy to feel frustration when an administration you like is in office and is hampered by these rules. But the system must be designed with a Rawlsian theory of justice14 and a tight veil of ignorance — the idea that systems must be designed in a way that avoids replying on what an individual’s position on a topic is. An informed opinion cannot be, “My guy or gal and their administrative state should be able to do whatever they want but the other guy’s oh, no no no!”

Carveout: Rent Moratoriums and COVID-19

There was a recent case that showcases this tension between desirability and legal authority on an issue of great importance — rent moratoriums during the COVID-19 pandemic — that related to agency authority.

The CDC issued a rent moratorium for a particular subset of the population at the end of December 2020, after the rent moratorium passed by Congress in the second round of the CARES Act was due to expire. A group of landlords in Alabama, the Alabama Association of Realtors, sued the CDC, saying that it exceeded its authority.

Let's get this out of the way: It’s tough to argue against the fact that rent moratoriums were a good idea. In the face of a struggling economy during the COVID-19 that led to the people who have the least to have even less, it made sense to enact rent moratoriums for folks who may have lost their jobs and were barely making ends meet. Congress had also allocated a bunch of money to help landlords with at least part of their lost rents.

But the question before the court was not whether the rent moratorium was a good idea, but whether the CDC — the Center for Disease Control and Prevention — has the authority to issue a rent moratorium. The CDC is a public health agency. How in the world could you argue that it has authority over rental decisions?

Even so, the CDC tried. It quoted this part of the Public Health Service Act of 1944:

The Surgeon General, with the approval of the [Secretary of Health and Human Services], is authorized to make and enforce such regulations as in his judgment are necessary to prevent the introduction, transmission, or spread of communicable diseases from foreign countries into the States or possessions, or from one State or possession into any other State or possession. For purposes of carrying out and enforcing such regulations, the Surgeon General may provide for such inspection, fumigation, disinfection, sanitation, pest extermination, destruction of animals or articles found to be so infected or contaminated as to be sources of dangerous infection to human beings, and other measures, as in his judgment may be necessary.

You can see the authority that the CDC is trying to claim is under the “other measures” phrase. There is an argument that goes something like this: rent moratoriums would have prevented the transmission of COVID-19 because it is possible that some people who would have been evicted would have COVID that they could then pass on to others. Therefore, a rent moratorium is an “other measure” that the CDC can use to prevent this spread.

That makes sense in theory, but it’s certainly a very aggressive interpretation of that sentence. If you agree that rents are covered by the quoted section, then very little isn’t. As the Court said:

Could the CDC, for example, mandate free grocery delivery to the homes of the sick or vulnerable? Require manufacturers to provide free computers to enable people to work from home? Order telecommunications companies to provide free high-speed Internet service to facilitate remote work?

Again, all of these might be desirable for society, but that doesn’t mean that the CDC has the authority to do this. If you think that they should be allowed to, then ask yourself the question: “Would I be okay with such a broad mandate if the other party was in the White House?”

The court said that since this is a power that would lead to “vast economic and political significance”, it expects Congress to have given explicit permission to the agency to take such an action. Which it never did.

Drawing a line: Chevron vs. Major Questions Doctrine

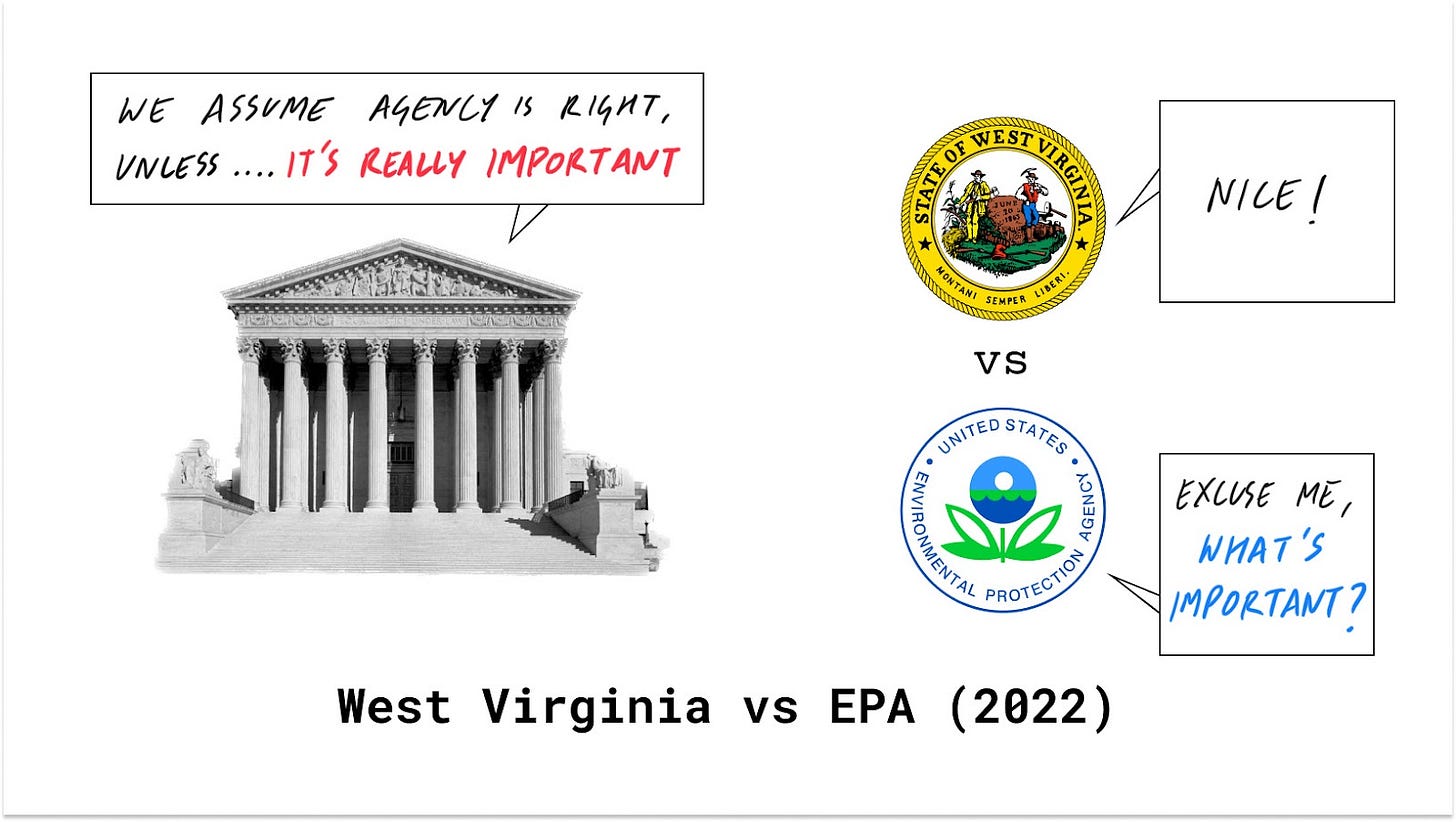

And the current Supreme Court would agree with the fact that agencies cannot fill out legal blank checks with whatever authority they want to draw on from the bank of laws. In 2022, West Virginia and nineteen other states said that the EPA did not have the required authority to mandate the transition from fossil fuels to other forms of clean energy.

The Supreme Court said that while the EPA did have the authority to regulate greenhouse gas emissions, it could not force companies to change the overall mix of electricity production because that’s just too big of a deal. If the agency had the power to do that, then what couldn’t it do in the name of regulating greenhouse gas emissions? Could it, for example, order planes to stop flying because they have emissions? Could it ask people to not drive outside the hours of 8am and 8pm?

In doing so, they invoke the Major Questions Doctrine:

When agencies seek to resolve major questions, they at least act with clear congressional authorization and do not “exploit some gap, ambiguity, or doubtful expression in Congress’s statutes to assume responsibilities far beyond” those the people’s representatives actually conferred on them. As the Court aptly summarizes it today, the doctrine addresses “a particular and recurring problem: agencies asserting highly consequential power beyond what Congress could reasonably be understood to have granted.”

It is possible to think of the Major Questions Doctrine as a version of the first step in the Chevron Doctrine: “has Congress spoken explicitly to the authority that the agency is claiming?” If Congress had thought that it was important (and thus under the agency’s purview), it would have spoken to it explicitly. You can also think about it as the second step of the Chevron Doctrine — the agency’s construction is not reasonable because Congress hasn’t authorized it. You can also just ignore Chevron altogether and note that since it’s so important, it's improper to give an agency automatic deference.

In this case, the dissenting opinion15 was scathing. To pick just one quote:

Some years ago, I remarked that “[w]e’re all textualists16 now.” It seems I was wrong. The current Court is textualist only when being so suits it. When that method would frustrate broader goals, special canons like the “major questions doctrine” magically appear as get-out-of-text-free cards.

It’s true that the Major Questions Doctrine is a sort of a deus ex machina for the court to say in any case related to agency actions, “You know, the vibes here are just not right.” and rule against the agency. In that, it is a blunt and highly discretionary tool of legal authority (see notes above about accountability of the judiciary).

But the Chevron Doctrine as it stands presents legal problems too. Primary among them, it fails to distinguish between actual discretionary powers granted to the agency by Congress and a case where the agency is filling in the legal blanks. Its simplicity is seductive, but it ultimately leads to an unsatisfactory balance of power outcome.

So just like a bank that might decrease your credit limit if you don’t make regular payments on a credit card bill, the Major Questions Doctrine is a way for the Supreme Court to limit the size of the blank check that was written to the administrative state in the 1980s.

Lessons learned

It’s true that the reduction of the scope of the Chevron Doctrine via the Major Questions Doctrine makes it less important in administrative law, and ultimately in day-to-day life. But there are broader lessons here about how systems work that are worth cataloging.

First, it’s an important object lesson that there are pockets of power in the government everywhere. Political power in a liberal democracy should emerge at the ballot box. But if you have a large country, you have to, at some point, deal in abstractions. Authority has to be delegated down the rungs of government. But at what point do the abstractions and delegations become so abstract that they have no relation to the ballot box? It’s an ever-changing balancing act that requires each part of the government to be functioning as intended.

Second, there is an interaction effect with a dysfunctional Congress that was likely never considered by the founders of the country. In theory, there could always be updated versions of key legislation like the Clean Air Act that are passed by Congress to keep up with the most important advancements. But this has not been a productive time for Congress. When one part of a carefully designed system does not work as intended, it can lead to poor outcomes for the broader system.

Third, there is a personal lesson to be drawn from this dangerous dance of governmental delegation. In my experience, the most successful people I know are deeply aware of their personal delegation doctrines — what and what should not be delegated to others. They are very, very good at this judgment call. Delegating gives you a lot of leverage; you can get a lot more work done if you can bring others along with you on a journey. But you cannot delegate the most important things. By discovering this line and discovering it early, you can be most effective, not just efficient.

Lastly, the fact that such a doctrine exists, impacts most people living in the United States and is yet not spoken of outside the small halls of government is a travesty of civil education in the country. But a similar scathing statement could also be made of most countries in the world. David Foster Wallace once said, “The most obvious, ubiquitous, important realities are the ones that are hardest to see and talk about.” So, the question is, how do we develop and maintain a rigorous program of civil education in a democracy? And what should your role be in developing and maintaining that program?

That perhaps, is a major question for us all.

Many thanks to Varun Sharma and Michael Hodak for all the help editing this piece.I’ll never be a lawyer, but perhaps the geekiest thing I enjoy is reading Supreme Court opinions. They are surprisingly accessible and like anything else, once you’ve read a few cases, you start to see how they are structured. It’s a weird thing that actually exists in every other domain, but since the law has to be standardized, it’s easier to see this underlying structure, at least at an amateur level.

If you're in any other part of the world, you probably have a similar government agency overseeing the safety of food and drugs sold in the country.

Self-indulgent side note: Probably my favorite type of feedback that I get from readers of the newsletter is that they appreciate the non-assumption of U.S. context, especially when it comes to writing about the government.

The President can also issue executive orders and while they have the force of law, they are not legislation. Only Congress can legislate. Executive orders also stand lower in the hierarchy of laws compared to the Constitutions and the laws passed by Congress.

This is the concept of judicial review as laid by the famous Supreme court case Marbury vs. Madison: “It is emphatically the province and duty of the Judicial Department to say what the law is.

Famously dysfunctional, so much so that when it does function, entire books can be written about it that go on to win Pulitzer Prizes.

The Federalist Papers were written to encourage states, in particular New York, to ratify the Constitution of the United States and are primarily composed of essays explaining the thinking behind many of the Constitution’s key structural decisions.

This change was due to a change in Presidential administrations — from President Carter to President Reagan, whose deregulation agenda could be inferred from his opt-repeated line: “Government is not the solution to our problem, government is the problem."

There is a whole separate strand of thought that says that the advent of nuclear weapons is what is most responsible for the expansion of the administrative state. Given the technological limitations and short timelines on which decisions have to be made, the President has the authority to order a nuclear strike. The argument goes: If you’re going to give the President the authority to create a global nuclear winter, why not give him authority to do a whole lot more than that across various parts of the government? It’s an interesting strand of thought and gets to philosophical questions and those related to path dependence — in other words, it’s a discussion for another time.

The Chevron Doctrine is generally liked by whichever party is in the White House since it controls the executive agencies. There is likely more of a permanent soft spot in the Democratic party towards the doctrine since generally, it favors more regulations.

Or bug, depending on your stance on the appropriate size of government.

OIRA is the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs — a dull name that hides a ton of influence since every regulatory action needs to be approved by this body.

In 1832 when the Supreme Court under Chief Justice John Marshall ruled against him in the case, then President Andrew Jackson supposedly said, “John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it.”

I’ve quoted enough old, white men here that I’m half expecting a young Matt Damon to jump out at me from this page and start off with “Of course that’s your contention.” and tell me why everything I’ve said has been rebutted and explained away to no end. And that may be true, but that shouldn’t stop me from explaining in plain English the issues at hand here.

Since there are nine Justices on the Supreme Court, decisions are rarely unanimous. Often, the minority will write an opinion known as the “dissent.”

The current Supreme Court has a Conservative majority which prefers interpreting laws as they are written in the text, ignoring its intent and history. This is known as textualism and can be contrasted with legal realism which considers social interests and broader public policy goals when interpreting the law.