Why is flying not sexy anymore?

A short-ish political history of airline regulation in the United States and what we can learn from it

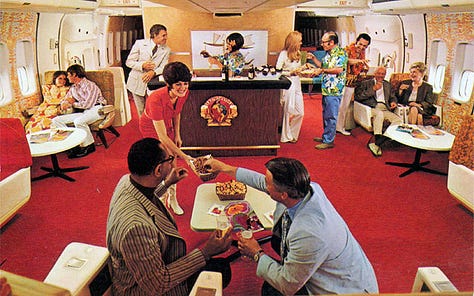

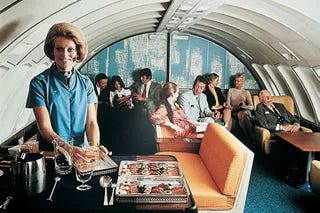

My favorite section of a used book store is the art books — they offer me a chance to pick something up that would be way too expensive otherwise. A few weeks ago, I was perusing a nook at a local bookshop in London and came across Airline: Identity, Design and Culture by Keith Lovegrove1. As I flipped through its pages, the photos of airplane interiors from the 60s and 70s exuded a sense of glamor and elegance. It makes you think that if you were alive then, you too would dress up in your tweed sport coat and dress shoes, breeze through a TSA-free airport and feel like Don Draper from Mad Men in your plush leather seat.

Of course it is tempting to wish for this bygone era of luxury and decadence. When cocktails and lobster were served in real glasses and real plates. And you could often get this on a coach ticket.

You want to go back to this golden age of no hawking of credit card offers2. Where you didn’t feel the need to drown it all out with noise-canceling headphones after you’ve been given your measly rationed Biscotti and water. Forget coach, not even the paid-thousands-of-dollars-because-their-company-is-covering-it First Class folks are spared today — they make the announcements from the front row!

So what the hell happened?

How did we end up in this alternate dimension where it seems like a new episode of QVC is being filmed on your airplane during every flight? And how did piano bars, exquisite lounges, and just plain old dignity get stripped from American aviation?

In short, why is flying not sexy anymore?

The story here is one of de-regulation, revealed preferences, and political ambition. It’s also one of how government intervention can both support and hinder the growth of an industry. Importantly, as we go through the evolution of the industry, you will fee; a sense of inevitability towards the forces of deregulation. But how and when that deregulation happened is the story of how the grandest ambitions — judicial and presidential — of a few people breathed life into economic forces.

It’s a story that takes us through the decades from the wild west of the 20s to the New Deal to the booming 50s and 60s and culminates in the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 and its aftermath. We will end up with lessons not just for the regulation of the airline industry, but for the broader concept of government regulation of fast-moving technological forces.

Let’s dig in, starting with a basic history of the industry.

Take off: 1920s to 1938

Airplanes are beautiful, cursed dreams, waiting for the sky to swallow them up. — The Wind Rises

Ever since the first flight at Kitty Hawk by the Wright brothers in 1902, airlines have represented one of the pinnacle achievements of mankind. The power to fly across large distances has been transformational to the socio-economic makeup of the world. In the United States, the development of the airline industry for the first two decades after Kitty Hawk was haphazard. The military funded development and production of aircraft during World War 1, but it was only after the war wrapped up that the government took a proper look at what was happening in the “industry” — if you could call a bunch of uncoordinated routes and dangerous landings an industry. What it saw was that in a world where going up in the air was more for adventurers than for businessmen (with a fatality rate of 1 death per million mile3), airmail was the baby food that the industry was growing up on. No less a personality than Charles Lindbergh4 was the chief pilot on the St. Louis — Chicago airmail route.

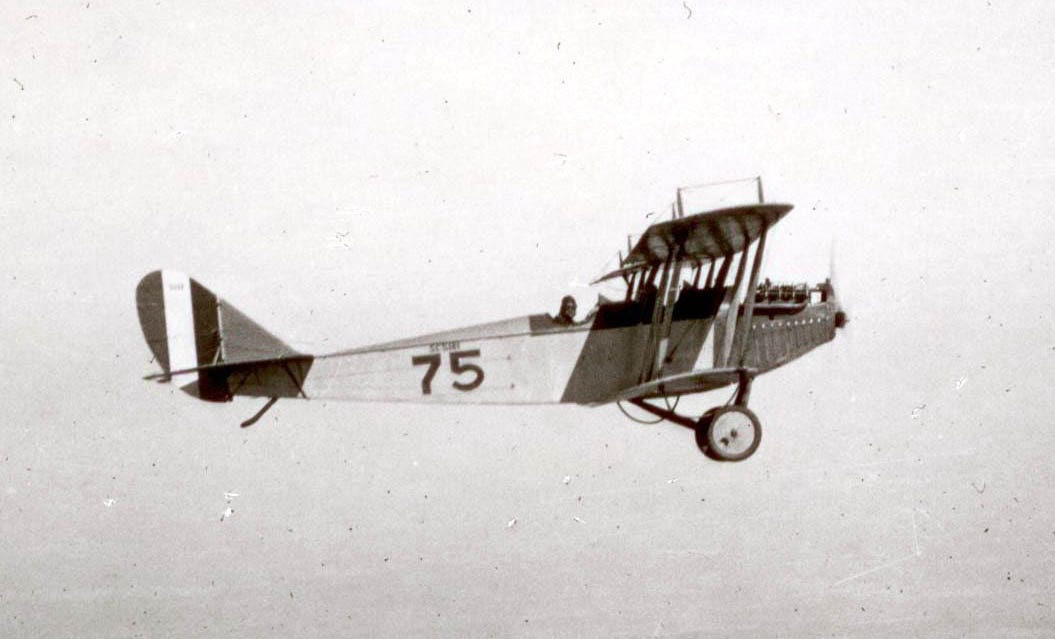

Looking at this uncoordinated and dangerous situation, the 68th Congress passed the Air Mail Act of 1925 which primarily served to create a system of competitive bidding and subsidies for airmail service that airlines could bid on. While these subsidies were on the order of $7 million per year by 1930 and stimulated demand for airmail services, the competitive bidding process meant that profits were paltry. This means that (1) they didn’t make any money which tends to make businessmen unhappy and (2) there was no excess capital that could be reinvested into the industry to make aircraft better. This reinvestment was critical as the pinnacle of airline technology at this time was the Curtiss JN-4, which had two seats and a small cargo hold.

Unhappy, the major players at this time complained to the person in charge of airmail, the Postmaster General of the United States.

In response, the Postmaster General at the time led a campaign to give himself the authority over routes and mail rates in 1930. This was — in line with the political power that the Postmaster General could flex at this time5 — a successful campaign. The McNary-Watres Act of 1930 gave him complete authority over the nascent airline industry. Just as soon as Congress had christened him as the Godfather of the skies, he got all the major players together in what was later called the “Spoils conference” and divided the country into three areas — giving the southern route to American Airways, the central route to Trans Continental and Western Air, and the northern route to United Airways. This was, in effect, a cartel with the full backing of the United States Congress.

Obviously, this was not great in principle — one man ruled supreme when it came to the skies and he could dole out patronage to whoever he wanted. But the noncompetitive bidding for the mail contracts allowed passenger service to grow as improvements in aircraft technologies were made from excess profits. For instance, for the first time ever, there was a New York to Los Angeles route, made possible by larger bodies and a less bumpy ride.

But it was not politically sustainable. When people learned of the back room deals that the Postmaster General had cut, there was a scandal in Washington, DC. Congress stripped the Postmaster General of his dictatorial powers over the skies of the country in the Black-McKellar Act of 1934 and made it a lot harder for existing carriers to bid on new contracts. As if on cue and no longer getting the highest level of subsidies, the industry started to operate at a loss.

With a new President — Franklin D. Roosevelt — came the new ideology of the New Deal6 and the regulatory fever of the thirties was contracted by the airlines as well. One of the operating principles of this ideology was the idea of a goldilocks zone of regulation — there should be enough competition for companies to innovate, but not so much that they don’t have the money to do so.

With this in mind, Congress passed the Civil Aeronautics Act of 1938 which created the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) under the Department of Transportation as the regulatory body for the airline industry.

A quasi-political entity, the board had the power to control entry and exit, approve or modify ticket rates, set mail rates, control mergers, and optimize methods of competition7. It consisted of 5 members appointed for six year terms by the President with the consent of the Senate. It had a chairman (chosen by the President) who directed bureaucrats under him or her. It had two broad objectives: to both regulate and to encourage the growth of the airline industry.

The stage was set for the next 40 years of the airline industry.

Plenty of turbulence: 1940s to early 1960s

“Indeed, if a farsighted capitalist had been present at Kitty Hawk, he would have done his successors a huge favor by shooting Orville down.” — Warren Buffett

After World War II ended, there was a glut of pilots (more than 250,000 pilots were trained during the war period). If you can fly a Lockheed L-29 fighter plane over Tokyo, there is no reason why you couldn’t fly a Douglas DC-4 over Toledo. The number of pilots was often a limiting factor, but the industry now had the pilots to fly the planes. All that was needed were new routes for the CAB to approve.

And approve routes the CAB did. It doubled the number of miles in the airline network of the United States between 1938 and 1955. Better yet, many of these new routes were going to smaller carriers and the share of the Big Four of the airline industry (American Airlines, United Airlines, TWA8, and Eastern Airlines9) at the time went from 81% in 1939 to 71% in 1954.

But the initial report card for the CAB was not just A-pluses down the sheet. It struggled to balance technological advances (note that airplanes were improving rapidly during this time period) and macroeconomic realities with its objective of a fixed utility-style rate-of-return for the airlines of around 10-12% across the entire industry.

This led to a low load factor10 of approximately 50-60%. Planes were flying half empty.

This entire system was doomed to fail because the airlines couldn’t dynamically change prices to meet the rate of return objective. Those too were set by the CAB. When this regulatory straitjacket and the technological necessities of a still nascent industry met the wrong curve of the business cycle, economic disaster ensued.

One such example was what happened in the late 1940s.

During World War 2, the predominant passenger plane in the United States was the Douglas DC-3, a 21 seater propeller plane. The next generation of aircrafts included the Douglas DC-4, a 44 seater four-engine plane, and the Lockheed Constellation with a pressurized cabin and 37 seats. These were meaningful advances in passenger capacity and experience back in the late 1940s, and the airlines wanted these planes.

To finance the transformation of their fleets, airlines took on debt. But in 1948, there was a brief recession and the industry was hard hit — passenger volume went down and operating margins turned negative.

In response, the CAB made the carriers increase these fares by 10% and shut the door to new entry for almost the next 10 years. Only by the mid 1950s when seats were being filled at these higher fares (driven by the booming 50s) would this ban on new entries be lifted under new chairman appointed by the new President, Dwight D. Eisenhower11.

This was a blueprint of how the CAB would regulate the industry for the next three decades.

Its response basically ran counter to the prevailing business cycle. When business was bad, it would ask airlines to increase fares and add subsidies to specific routes. When business was good, it would loosen restrictions to new entry. Almost by definition its policy prescriptions were always too little too late and the airlines had no choice but to follow them.

This blueprint was followed almost to the T again when another transformation of the airline industry’s fleet occurred with the advent of the jet age. Pan Am12 ordered 20 Boeing 707s and 25 DC-8s which could seat more than 100 passengers. Overall, the industry committed to more than a billion dollars in new equipment which added capacity and debt. To finance this, the CAB again increased fares first by 10% in 1958 and then by 5% in 1960.

Again, the airlines had little to no control in setting or changing these prices. This discouraged cost effectiveness and didn’t offer much in the way of customer choice. If you could afford to fly at these expensive rates, you did. If not — and most couldn’t — then that’s too bad, said the CAB.

It’s worth mentioning here that this was not all bad. By coddling the industry with a fixed rate-of-return, the CAB ensured that technological innovations were always financed. From the DC-4 to the Boeing 707 to the DC-10 and the Boeing 747, the airline industry could always fall back on the ever higher fares set by the CAB. While terrible for the customers at the time, these advancements led to the development of the airplanes of today.

But even though the competitive urges of airline executives at the time could not find economic channels, it still found avenues of expression.

Even though prices was fixed, how did people decide which airline to fly? Well, sometimes there was only one airline on a particular route in the regulated world. So you didn’t have much choice. Sometimes, you had multiple airlines but there was only one that worked for your desired departure or arrival time. But on a popular route like New York—Chicago, there may be many airlines with similar departure and arrival times. How could an airline — say United — entice you to choose them when you would be paying the same price to American Airlines to go to the same place at the same time?

They could do so by making the flying experience luxurious — enter the “lounge wars.”

When the skies were luxurious: Late 60s and early 70s

The focus on “service competition” — focusing on the customer experience of flying — was always important with flying as the primary customers were wealthy businessmen with discerning tastes. It was even more important to differentiate yourself by your service when there was no difference in pricing between you and your competitors and this uniformity was mandated by the government.

But until the 1960s, airplanes were just not large enough to build anything inside them. So service competition was focused on making the individual customer feel special. This includes large seats, great meals, and the general hospitality. But this was not the golden age of decadent lounges and cocktail clubs in the air.

That was enabled by the wide-bodied jets in service by the late 1960s, when airlines started to take out seats from large portions of their aircrafts which left them with enough space to put in other things to attract customers.

Some of these included:

American Airlines installed piano bars with audience seating and in-flight movie projectors on their longer routes

TWA countered with electronic draw poker machines13

Continental Airlines had a bar in economy class called the politically-incorrect “Polynesian Pub” along with arcade games

Southwest Airlines, then a plucky upstart, paired its tickets with a full-size bottle of whiskey. At one point, it was the largest distributor of Chivas Regal in the state of Texas!

Passengers in coach on Southern Airways, known as the “Route of the Aristocrats”, were served complimentary glasses of Champagne along with a souvenir shot glass

It was the combination of government price regulation and the technological advance of larger, wide-bodied jets that enabled this expansion of luxury in the air. Some of the installations even explicitly played off CAB guidelines. For instance, even though seats were taken out to create space for a piano bar, the load factor calculations of a flight that the CAB assumed that the original seats were still there.

But these extravagances of businessmen with seemingly unlimited expense accounts were not sustainable. For they were about to meet the harsh economic realities of the early 1970s.

In 1973, an oil crisis was precipitated by the OPEC countries’ embargo of the shipment of oil to nations that had supported Israel in the Yom Kippur War. It translated into a 200-300% increase in the price of oil for a period of time. Combined with rising inflation, lower growth, and higher interest rates during these years, passenger demand plummeted. The CAB tried to counter by reducing the number of weekly flights by 10-38% across different city-pairs (reducing capacity would mean that more flights were more full and the airlines could continue to operate at a profit) with little to no impact.

This economic crisis of the early 1970s dovetailed with a more metaphorical — but still very real — crisis of the American public’s confidence in its government. This was the time of Vietnam and Watergate. A time when you didn’t need to fear just fear itself, but you would have had good reason to fear the crook in the White House. A time not too far away from the “Government is not the solution to our problem, government is the problem” days of Reagan.

In the midst of all that, a government agency setting extremely high fares and the top 1% engaging in karaoke in the air offended the nation’s sensibilities.

In particular, there was concern of the CAB — the regulatory body for the airlines — being “captured” by the airlines. This perception was created by (1) news leaking of closed door meetings with airline executives and CAB members where the public was not represented, and (2) a revolving door of employees between the CAB and the airlines.

Stephen Kotkin, most famously the author of the three-volume biography of Joseph Stalin, talks about how history is determined by structures and agents. Structures are the historical forces that make certain events almost inevitable. Agents are the people who give the forces a final push to make the events happen.

With the mismanagement of the airline industry under the CAB and broader political winds, the structures and conditions that could precipitate a call for the deregulation of the airlines were set by the early-1970s.

But critically, nothing happened. For it was not in anyone’s — at least no one with any influence — interest yet. The political will was the limiting factor to any changes in the airline industry.

For the agents were missing. But they would not be missing for long.

The Professor and The Lion: 1973 to 1978

When an East Boston constituent asked Ted Kennedy, "Senator, why are you holding hearings about airlines? I've never been able to fly," Ted Kennedy replied: "That's why I'm holding the hearings."

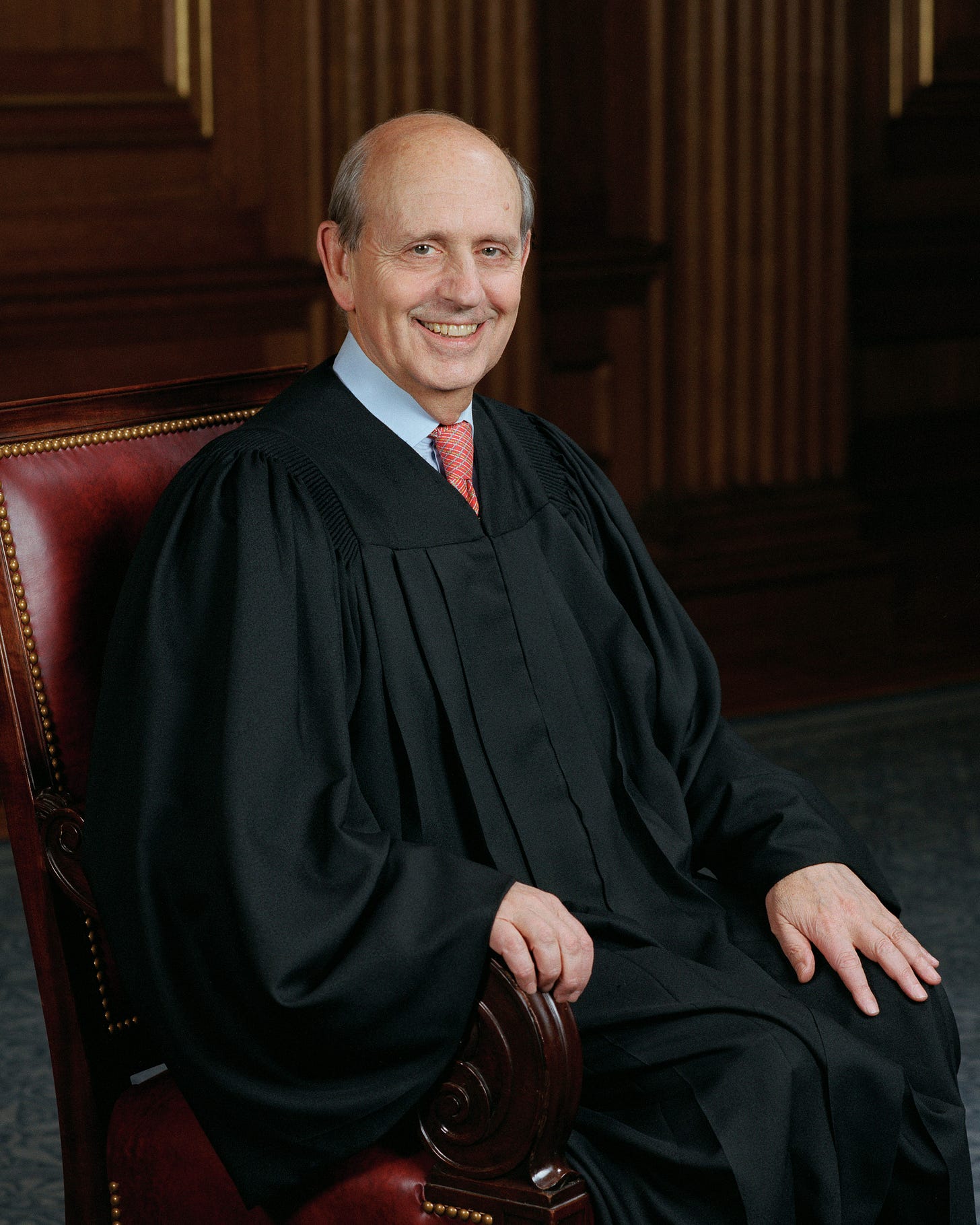

If you walked along the dreamy corridors of Harvard Law School in 1973, one could find one such agent of upcoming events in a spry, almost-40 year old professor named Stephen Breyer14. Up until this point, Breyer had been an academic with a bent towards the commercial side. He had written extensively about deregulation in books like Breaking the Vicious Circle: Toward Effective Risk Regulation and Regulation and Its Reform, the latter of which was a hit in policy circles. Yet, despite his interest in the commercial, his ambitions were judicial and he would take frequent leave of absences to work on special projects for Washington insiders15.

Breyer knew through his research that airline deregulation could be an attractive political project. It had visibility and glamor (with the fancy lounges and all) for the broader public. It would be achievable too: neither the firms nor the unions were strong enough to resist a true push from Congress16, compared to other similarly regulated industries like trucking where the Teamster union reigned supreme.

But Breyer was just an academic. In order to bring these ideas into the light and to make a name for himself, he would need someone with political power. And he found someone not just with power, but someone with the power of the most famous last name in the country.

Ted Kennedy was younger than John F. Kennedy and Robert F. Kennedy. He did not have the charm nor the intellect of his elder brothers. But he had the name. And on top of that name and a rock solid Senate seat in Massachusetts, he had built a portfolio of impressive legislative accomplishments tackling meaty liberal issues like civil rights and healthcare. He eventually came to be known as “The Lion of the Senate” for these contributions.

If Breyer’s ambitions were judicial, Kennedy’s were presidential. The Chappaquiddick incident in 196917 meant that he had not run for president in 1972, but he was eager to rebuild his image.

Kennedy knew many of the professors at Harvard, but it is also possible that Breyer and him met through one of Kennedy’s legislative aides who was a classmate of Breyer’s. When Kennedy asked for ideas that Breyer was interested in, the professor had airline deregulation at the very top of his list.

In airline deregulation, Kennedy saw a topic that voters could get behind. And unlike his other causes, this one would be popular with Conservatives (whose votes he would need if he ever wanted to be President) and help provide a common sense streak in his otherwise liberal image.

Along with a topic, he had a forum too. A forum he had created in the non-descript Subcommittee on Administrative Practice and Procedure under the Judiciary Committee, one of the 15 standing committees18 of the Senate. Its vagueness could have meant that it did not have jurisdiction over anything meaningful. But Kennedy turned this weakness into a strength and the subcommittee seemingly had jurisdiction over everything meaningful to the liberal cause that did not fall under the obvious purview of the other committees. In recent years, it had investigated issues like racial bias in the policies of the Defense and Transportation Departments (1969), the Selective Service System19 (1970), clemency for Vietnam War evaders, changes to the Freedom of Information Act, and other similar topics.

With this bully pulpit in the subcommittee and a deregulation expert in Breyer, Kennedy set hearings on the question Has regulation produced higher fares? in relation to the CAB in February 1975. In August 1974, Breyer took another sabbatical from Harvard to come work for the subcommittee.

But it was not going to be an easy fight. While the airlines occasionally suffered because of the policy whims of the CAB, they knew the devil they were dealing with and knew how to deal with it. They preferred the status quo. Congressmen were also eager to keep the high paying jobs that regulated airlines offered in their districts. De-regulation as a concept was new too, and there was concern around what it might do to a system that was falsely described as “the finest air transportation system” by the airlines.

Kennedy and Breyer had to be strategic.

Breyer first mobilized allies within the Executive branch — this being the Republican administration of Gerald Ford — who were philosophically hostile to government regulation of the airlines. He wanted to invite these experts from the Department of Justice’s Antitrust division, the Department of Transportation, and the Council of Economic Advisors to testify in front of the subcommittee to give the hearings a flair of bi-partisanship.

These were highly choreographed affairs. For example, one of the witnesses was John W. Barnum, the General Counsel for the Undersecretary and Deputy Secretary of the Department of Transportation, who later recalled a moment from the hearings:

Senator Kennedy started to quibble with some of my answers to the questions that his counsel [Stephen Breyer] had prepared for him to ask, and his counsel poked Senator Kennedy in the ribs and said with an audible whisper:

"That's the right answer, Senator. Ask the next question."

Breyer also prepared questions for the airlines to answer. This included questions on airline policies, revenues, costs, purchases, training programs, and general administrative procedures. To make sure that the hearings had the air of fairness (and to genuinely hear the other side of the arguments), this input from the airlines was critical.

Another group that Breyer reached out to was the CAB. He asked them around 50 questions around agency decisions, procedures, meetings that the CAB had with industry representatives, and other such concerns.

Breyer knew that the Senator had to tell a story to the other legislators and the American public — that of ineffective and potentially corrupt government regulation that was keeping fares high and strangling the full potential of the airline industry in serving the needs of the country. He structured the hearings such that the first day would present a problem, and the succeeding days would explore a particular aspect of the problem and how the CAB addressed it.

To tell this story, he also involved the press. Hearings were usually dull affairs, so a certain level of humdrumming of interest was necessary. In January of 1975, he met with reporters from the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the wire services and other publications. This would ensure that when the hearings would take place in a month, there would be adequate coverage.

The six days of hearing provided an opportunity for consumers, airlines, the CAB itself, experts from the government, and other prominent figures to present their views. Kennedy’s kickoff speech on day one summed up the thrust of his arguments:

Regulation has gone astray. Either because they have become captives of regulated industries or captains of outmoded administrative agencies, regulators all too often encourage or approve unreasonably high prices, inadequate service, and anticompetitive behavior. The cost of this regulation is always passed on to the consumer. And that cost is astronomical.

Through careful preparation on Breyer’s part and political machination on Kennedy’s, the hearing was a resounding success. Though the CAB was still likely not a household name, the public was now aware that it was responsible for sky high fares.

The next two years were spent on more hearings. These dove deeper into the issues presented in the first one. The time also offered the airlines to craft a response through substantive pushbacks on the real concerns of de-regulation and political leverage.

The airlines were generally opposed to de-regulation, but some in the industry knew that there could be advantages to it. United Airlines in particular was aware that their larger size — they had the largest fleet of airplanes and the most number of routes — meant that they could likely come out of deregulation with a stronger position than before. Smaller airlines like Southwest also preferred deregulation. Medium sized firms like American Airlines were concerned that they would be squeezed out. Then head of marketing for American and later its CEO, Bob Crandall, was heard after one round of hearings saying:

You fucking academic eggheads! You’re going to wreck this industry!

But no matter how much success he had had in making his pet project through his pet subcommittee a national topic through the hearings, Ted Kennedy was just a Senator. And in modern American history, while the engine that converts the will of the people into the statute books is Congress, the fuel for that conversion is usually provided by the Executive branch — the President. And in 1977, there was a new one in town20.

The Peanut Farmer deregulates the airlines

Jimmy Carter was elected to the White House mostly because he was a good man. He was a clean break from the crooked President who insisted until the end that he was not crooked and his Vice President-turned-President who had the unenviable task of getting the country past Watergate.

Carter and Kennedy were not natural allies. Kennedy would have likely run against Carter in the Democratic primaries in 1976 had it not been for that one night in Chappaquiddick. He could have been President instead of Carter and always loomed large as a potential rival to him.

But Carter was probably the least-plugged-into-DC person — he was previously Governor of Georgia — who was ever elected President. He didn’t know how to get things done in the city. How to get things done in Congress. But Ted Kennedy did.

So when the President’s transition team was looking to identify what could be quick economic wins for the administration, airline de-regulation and Ted Kennedy came up.

In March 1977, less than two months into his Presidency, Carter sent a message to the Speaker of the House and the following (along with guidance on what the parameters of the law should be) was inserted into Congressional Record21:

As a first step toward our shared goal of a more efficient, less burdensome federal government. I urge the Congress to reduce Federal regulation of the domestic commercial airline industry.

With the President and Congress aligned, the airlines divided, and plenty of political futures to be made, there was one final roadblock. While the airlines’ workers unions were nowhere as strong as the trucking Teamsters, they were still formidable. And if they were opposed, the de-regulation bill could lose steam very quickly. But supporters of deregulation converted the unions to their cause by proposing and including a provision that prohibited “mutual aid” that airlines could provide one another if one of them was facing a strike. This was a large miscalculation. Of all the losers of de-regulation, the pilots and workers of the airlines would lose the most. Over the years, an onslaught of competition cut wages and benefits across the board.

While the backroom deals continued to get struck in exchange for support for the legislation, the President continued his. In his 1977 State of the Union address, he declared:

But I know that the American people are still sick and tired of Federal paperwork and red tape. Bit by bit we are chopping down the thicket of unnecessary Federal regulations by which the Government too often interferes in our personal lives and our personal business. We've cut the public's Federal paperwork load by more than 12 percent in less than a year. And we are not through cutting. We've made a good start on turning the gobbledygook of Federal regulations into plain English that people can understand. But we know that we still have a long way to go.

When the Airline Deregulation Bill of 1978, introduced as S. 2493, reached the floor of the Senate on April 19, 1978, it passed by a vote of 83-9. It passed the House on September 21, 1978.

On October 24, 1978, Jimmy Carter was flanked by Ted Kennedy, the new Chairman of the CAB Alfred Kahn, and airline executives as he signed the bill into law. Carter noted how rare it was to deregulate an industry22 — ““For the first time in decades, we have deregulated a major industry” — and in the style of the last president who had something to say about the airlines seemed to say that happy days were here again.

The airline executives may have been smiling at the bill signing out of politeness, but they had good reason not to be — they were in for a bumpy ride.

Adapting to the new world

This preservation of favorable variations and the rejection of injurious variations, I call Natural Selection. — Charles Darwin

While airline executives in 1978 did not have Darwin on their mind, they did follow his principles. Adaptations were necessary.

Most adaptations to deregulation were made based on the size of the airlines making them.

Larger airlines like United and American Airlines adopted strategies through which they could take advantage of their size. Instead of schmoozing CAB officials, they invested in things like booking systems like APOLLO (United) and SABRE (AA) where their scale allowed them to sign up travel agents that worked indirectly for the airlines. For these larger airlines, it was also a waiting game — they knew that at least some smaller airlines would struggle with deregulation and go bankrupt. This would allow them to acquire defunct assets and routes on the cheap. For example, American Airlines acquired Air California in 1987, Eastern Air Lines in 1990, Trans World Airlines (TWA) in 2001, amongst others. The overall industry saw such consolidation.

For smaller airlines like Southwest Airlines, deregulation acted as a tailwind to expand into newer markets and they were able to offer competitive prices to attract new passengers from legacy carriers. In fact, this expansion started the day the bill was signed23:

Once the bill was law, more than 2,000 dormant airline routes would be instantly up for grabs. The CAB intended to dole out the unused routes on a first-come, first-served basis. So a spectacle ensued in which corporate representatives lined up along the Connecticut Avenue entrance to the CAB like rock fans waiting to buy concert tickets.

Some adaptations were adopted by almost all airlines. For example, given that the CAB had previously approved each route individually, most of the airline network looked like point-to-point connections. With those restrictions gone, airlines started to adopt a hub-and-spoke model that allowed them to serve more city-pair combinations and to consolidate expensive operations in their hubs, further driving down passenger prices.

Another development was the worsening of service quality. Now that airlines were able to price their tickets at more or less any price they wanted, fares crashed. No more piano bars and playboy bunnies. Airplanes were not sexy anymore.

And with lower prices, passenger volume skyrocketed as it was now within the reach of an average person to take a flight every once in a while.

One final — and not often-discussed — consequence of deregulation was the preemption of any state-level consumer protection law by the Federal Deregulation Act. This means that even if a state adopted laws making it illegal for airlines to engage in say, deceptive airline advertisements, it would not be valid because it is “preempted” by the following clause in the Airline Deregulation Act:

A State, political subdivision of a State, or political authority of at least 2 States may not enact or enforce a law, regulation, or other provision having the force and effect of law related to a price, route, or service of an air carrier that may provide air transportation under this subpart.

Given that this preemption is made explicit in the Act, the Supreme Court has adopted an expansive view of Congress’ intent and not allowed state-level protections against deceptive airline advertisements (Morales vs. Trans World Airlines, 1992), devaluation of frequent flyer points (American Airlines vs. Wolens, 1995), or even a breach of the implied covenant of good faith (Northwest vs. Ginsberg, 2014).

While flying has become cheaper and within reach for most Americans, it is not glamorous anymore.

Lessons learned from Airline Deregulation

Let’s take a breather here. Note that when you fly, you spring almost half a million pounds of metal with a pressurized tube inside tens of thousands of feet in the air in a matter of seconds. To fly is a magical experience. It’s pushing beyond the bounds that nature has imposed on us. It’s a triumph of human achievement. Heck, we even have semi-reliable WiFi on planes these days!

With that healthy dose of perspective in mind, let’s get back to deregulation.

Whether this was good or bad depends on your point of view. On one hand, if you were one of the millions of people who had never stepped on an airplane because of how expensive tickets were, deregulation has been a huge democratizing force. On the other hand, if you were one of the businessmen whose large expense account paid for the lounges and piano bars, even first class today is a comparatively worse experience.

Regardless of where you are on that spectrum, most will agree that when the airlines were a transformative technology. And whenever transformative technologies emerge, there are immediate calls to regulate them. So what are the lessons that can be learned from the cycle of regulation and deregulation that the airlines went through?

Some of the following come to mind:

Change happens through aligning ambition with forces: The most important takeaway for me is how it takes many people working over years to make large change happen — in this case the deregulation of an industry after four decades of government control. While the economic conditions and evidence of the CAB’s incompetency had existed for a while, it was only when it was politically expedient for certain individuals’ own goals — for Stephen Breyer to become more of a DC insider on his path to a Supreme Court seat, for Ted Kennedy to build his resume for his Presidency that never came, and for Carter to establish his administration as one that gets things done — that political power was used to unshackle the airlines. AsBradley Tusk likes to say, “Every policy output is the result of a political input.”

Regulating complex systems have trade-offs: As we discussed, the airline flying experience might be worse, but more people than ever are getting to fly. In complex systems, there is usually no elimination of problems, just substitutions. It’s better to understand what side you want to be erring on and commit to the path.

The old versus new ways: The deregulation process started in earnest in 1974 and deregulation finally occurred in 1978 — a process that took 4 years. That was okay when it came to the airlines because it is by nature a slow moving industry with large capital expenditures and decade-long fleet cycles. But when it comes to the industries that are in the regulatory scope of the government today, most move in product cycles of months or weeks. And to suggest that Congress moves any faster than it did in the 1970s would make for the start of a really good stand-up joke. So a legitimate question to ask would be, “Is the current political system set up to regulate or de-regulation anything meaningful today?” I’m afraid the answer is no.

Ideological wave of the era: When the airlines were first regulated in a comprehensive manner, it was one of the last industries to be bound up in the style of the New Deal. When they were deregulated, it was the first strike in a ~20 year project of deregulation across American industries starting with President Carter and ending with President Clinton. If you’re a company in an industry ripe for regulation, it’s worth asking, “What are the broader ideologies in vogue when it comes to regulation?”

Stated vs. revealed preferences: Very rarely is the public’s preferences for cheaper and more frequent service revealed against the stated preference of more comfortable travel. Yes, it’s not fun to be packed up like sardines with comically little seat pitch, but if you don’t have all the money in the world you can take a 4am flight with the cheapest fare. We, as a collective, have decided through individual actions that we want this system.

Be flexible: The companies that survived deregulation were able to do so by identifying what characteristic about their business was uniquely suited to deregulation. For large companies, it was about making large investments that could be recouped over their larger customer base like travel booking systems and developing a hub-and-spoke model of flight routes. For smaller companies, it was usually an opportunity to expand into other markets adjacent to their current routes. You have to play to your strengths.

The history of the airline industry over the last 100 years shows that both regulation and deregulation created different problems, but my perspective is that only one regime allows most people to even experience it in the first place. In retrospect, truly luxurious air travel was a blip, existing for a period of less than a decade in the late 60s and 70s.

When we look at what governments around the world are most interested in when it comes to technology, two candidates come to mind — Big Tech and AI. It is wishful thinking to hope that the government will get the balance of considerations right in how they approach regulation for these categories.

If governments over-regulate, they will almost certainly stifle innovation. This doesn’t just mean that companies wouldn’t be able to take specific actions that would be economically helpful for a large part of the population, but also that there are certain actions that will be lost to the alternative history of the under-regulated universe. In other words, innovations that we will never know we lost. In today’s geopolitical environment, there is also a chance that other governments might go for fewer regulations and foster larger levels of economic gain for their countries:

Knots of War

Notes on US-China relations from a historical perspective and principles to guide the response of the Western world.

If governments under-regulate, at least with AI, there is a potential existential threat of an out-of-control intelligence. That’s not a bad argument for over-regulation if you can agree on a high-enough probability of this happening. For big tech, there is the risk of entrenchment and lack of competition through the economic influence they exert on the demand and supply-sides of the ever-expanding list of markets they participate in.

Obviously, it is not going to be easy.

In fact, I would argue that it is pretty tough for any institution or individual to decide conclusively what the right amount of regulation is for an industry. All one can have is a point-of-view, lay out the pros and cons, and be intellectually honest about their level of uncertainty.

All things considered, that’s not a bad way to approach any difficult task.

Thanks to Jackson Bubala and Albert Cai for their feedback on drafts of this essay.

Some of my friends in the FinTech space have mentioned that they love hearing these offers closely to see how they change and evolve over time. I guess the adage of “find what you love to do and never work another day in your life” really applies to them.

Compared to 0.0001 deaths per million miles today.

Later repudiated for his anti-sentimism, Charles Lindbergh was one of the world’s most famous people in the 1920s and 30s. His first non-stop solo transatlantic flight in 1927 led to a renewed interest in aviation after the disastrous security record of early airplanes.

While the importance of this position has understandably declined in the last few decades, it is difficult to underscore how politically important the Postmaster General was. The Postmaster General's decisions and policies had a direct impact on the efficiency of communication in the country which influenced economic growth and stability. It was also one of the jobs in the country which had huge patronage power, primarily when it came to giving away jobs in the postal service.

Driven by a belief that active government involvement was essential for fostering economic stability.

The original act in 1938 merged the safety and commercial operations of the airline industry. This was split into two in 1940 and the CAA (Civil Aeronautics Administration) — the predecessor of the modern FAA — was created to handle the safety regulations.

Acquired by American Airlines in 2001.

Liquidated in 1991 and its operational (landing slots, route approvals, etc.) and hardware assets (the actual planes, support equipment, etc.) were split amongst American Airlines, Delta Air Lines, Trump airlines, and others.

Number of seats occupied divided by total number of seats available.

Eisenhower is mostly interesting because he might have been the only person for whom the Presidency was a downgrade from one of his previous positions — that title being Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces, World War 2.

Primarily an international carrier which filed for Bankruptcy in 1991; most assets went to Delta Air Lines.

A rabbit hole that I had to keep myself from going under was the legal structure under which poker was played on planes. Since a plane could cross multiple state jurisdictions, did TWA have to get permission from every single one of these planes? Or was their a “skies are free for booze and gambling” provision that meant that the good times were allowed as long as you thousands of feet in the air?

Later known as Justice Stephen Breyer when he was nominated and confirmed to the Supreme Court in 1994 by President Bill Clinton.

One such leave was to serve as the Assistant Special Prosecutor on the Watergate Special Prosecution Force in 1973.

Another reason was that since intrastate (within a state) airlines were not regulated by the CAB, there were plenty of examples where a flight of a similar distance from California to Los Angeles was much cheaper than a flight from Washington DC to Boston.

In 1969, Senator Edward Kennedy drove his car off a bridge in Chappaquiddick, resulting in the death of his passenger, Mary Jo Kopechne. Kennedy failed to report the incident promptly, leading to controversy and speculation about the events surrounding the tragedy.

The 16th and final (as of this writing) standing committee, the Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship, was added in 1981.

An independent agency that maintains information on US citizens and residents who are eligible to be drafted in the case of a war.

To be clear, the preceding Ford Administration was also in favor of de-regulation and supported Ted Kennedy (even though he was of the opposing party) during the 1975 hearings. One of the ancillary lessons here is that you have to stay in power to be able to take credit for the work that you have done.

He would learn the lesson that Ford did before him — to do more of what you want, you have to stay in power. Since Carter was a one-time president, his successor Reagan would get to deregulate many more industries following the blueprint that Carter created with the airlines.

From the book Hard Landing by Thomas Petzinger.